Three Becomes One Becomes

or the shaping of a story larger than any human plant

Ein Beitrag von Leonie Brandner

This is the story of the Mandragora. It is the story of one plant that came into existence, grew out of proportion and into a belief system known as the ‘Alraunglaube’ (Mandragora belief). It is a story that emerged out of other stories of other plants, those of the Atropa belladonna, Paeonia officinalis and Rheum rhabarbarum. It is a story of witchery and tragedy, honesty and thievery, love, magic, hope and necessity.

This text traces the origin of the ‘Alraunglaube’ from Ancient Mesopotamia to modern times. It supposedly follows the trajectory of one plant, yet it tells us more about the human imagination, the ways in which our minds make sense of things beyond our control and the intricate ways in which human fate is tangled with the natural world, than it ever could tell us about any given plant.

by Leonie Brandner, 2022

The ‘Alraunglaube’

If an earth thief, who is born to steal because he comes from a thieving family, or whose mother stole when she was pregnant, or at least had a great desire to do so (according to others, if he is an innocent person, but confesses to being a thief in the ordeal) and who is a pure youth, the Mandragora grows where he is hanged and lets his water.

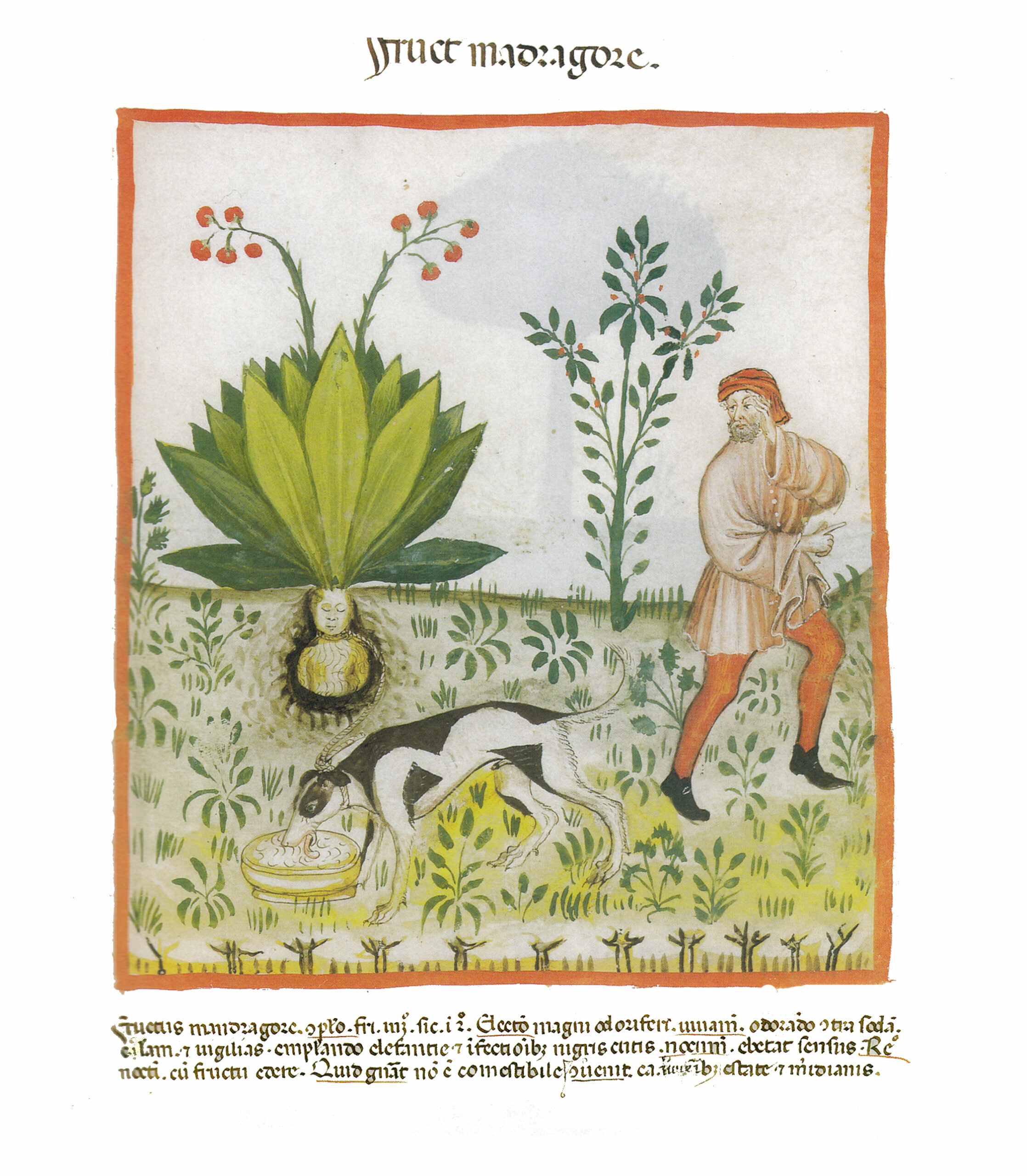

It has broad leaves and yellow flowers. There is great danger in digging it up, for when it is torn out, it groans, howls and screams so terribly that the one who digs it up must soon die. To obtain it, therefore, one must go out on Friday before sunrise, after protecting the ears with cotton, wax or tar, with a completely black dog, which must not have any other colours on its body, make three crosses over the Mandragora and dig up the earth around it, so that the root remains in the earth only with the smallest fibres. Then you have to tie it to the dog’s tail with a string, show him a piece of bread and run away in a hurry. The dog, greedy for the bread, follows and pulls out the root, but, struck by its groaning cry, soon dies. Then one can pick it up, wash it, clean with red wine, wrap it in white and red silk, put it in a box, bathe it every Friday and give it a new white shirt every new moon.

If one now asks the Mandragora, he answers and reveals future and secret things for welfare and prosperity. From now on, the owner has no enemies, cannot become poor, and if he has no children, he will be blessed with them. A piece of money, which one gives the Mandragora at night, is found twice in the morning; if one wants to enjoy his service for a long time and be sure that he does not stand out and die, then one does not overcharge him; one may boldly put half a coin to him every night, the highest is a ducat, not always, but seldom.

If the owner of the little Mandragora dies, the youngest son inherits it, but must put a piece of bread and a piece of money in his father’s coffin and have it buried with him. If the heir dies before the father, the eldest son is made the heir instead, but the youngest must also be buried with bread and money.[1]

‚The root was black but its milk similar to its flower:

[2]

The gods call it Moly, difficult to harvest

For mortal souls: but not so for the gods, who can do it.’

Moly. Across history there are rumours of a plant that is more than just plant; magical, potent, and otherworldly. Already in the Homeric Epos dating back to the 8th or 9th century BC finds the plant, moly, a mention. According to the legend, Odysseus is given the plant by Hermes, the messenger of the gods, to protect him from Circe’s magical transformation spells.[2] Yet the amount he was given wasn’t sufficient for all his men who found themselves exposed to her magic and transformed into pigs.[3] But what moly was, is, or can be, botanically as well as historically, is something that kept shifting over time. The plant shows up in antique literature under numerous names, ‘moly’, ‘baaras’, ‘circaea’, ‘morion’, ‘mala canina’ to name but a few that all described what later came to be known as the mandrake in English, the Alraune in German, or more generally across languages as the Mandragora. [2]

Thephrastus and the deadly nightshade

Botanically speaking, it all seemingly begins with one written account entitled ‘Mandragora’ noted by Theophrastus of Eresos in his Historia Planatorum, 350BC. He describes a Mandragora flour – a powder made from its root – which he prescribes as a remedy for sleeplessness, as a vulnerary drug, an aphrodisiac and even against podagra and erysipelas (gout of foot and a painful bacterial infection of the skin).[2] Depending on the dosage the plant was prescribed as a sleeping aid or as a narcotic in surgeries and during amputations[2] – uses that came to be a wide spread practice during the Greek Antiquity and beyond. In contrast to the straightforwardness of his described medicinal uses, his recorded harvesting rites read rather peculiar:

‘One is to draw three circles around the Mandragora with a sword and turn towards West while digging. Another should speak as much as possible about love matters.’

[2]

Love matters, matters of love. Despite recording the curious rite, Theophrastus expresses his skepticism towards it soon thereafter: ‘All this, as I said, seems to be inconsistent’.[4] Yet no matter how doubtful he was, he must have accredited a grain of truth to the rite, otherwise he could have left it out with good conscience.

Beyond the harvesting rites and medicinal uses, Theophrastus writes of a Mandragora growing as a shrub with black fruits containing a wine-like juice. [4] But none of the known Mandragora species grow any higher than just above ground, nor do any of them carry black fruits. It is to be assumed Theophrastus never meant the Mandragora we associate with the name today. Instead the plant he describes ominously sounds like the Atropa belladonna, commonly known under the name of the deadly nightshade – a close relative of the Mandragora and another member of the nightshade family.[1] Despite writing of a totally different plant species, Theophrastus’ contribution to the mythical existence of the Mandragora cannot be dismissed.

Flavius Josephus and the peony

Yet Theophrastus wasn’t the first nor the only one to be intrigued by the Mandragora. Over time, many a story and description was added to the Mandragora’s collection, one more fantastical than the next. Hard to attain and deadly upon touch, one Mandragora in particular was said to move, to fluctuate unsteadily from place to place, elusive and ungraspable, evading whoever approached. [1]

It was the first century Romano-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus who noted an account of said plant he referred to as ‘baaras’ – a Mandragora he located further East in modern day Jordan.

‘The valley which encloses the city of Machaerus on the north side is called Baaras, and produces a wondrous root of the same name. It is of flaming red colour and in the evening emits red rays; it is very difficult to pull it from the ground, for it eludes the approaching person and only keeps still if urine or menstrual blood is poured on it. Even then, death is certain with every touch, if one carries away the whole root in bare hands. But one gets it safely in another way and that is like this. It needs to be dug around in such a way that only a small remnant of the root remains invisible: then a dog is tied to it and if it wants to follow the tether quickly, it pulls out the root, but dies on the spot as a vicarious victim of the one who wants to take the plant. Once you have it, there is no more danger. However, so much effort is put into acquiring them because of the following characteristic. The demons, i.e. evil spirits of bad people, which drive into the living and kill them if help is not given quickly, are driven out by this plant as soon as it is even brought close to the sick person.’ [1]

Baaras, moly, all names the Mandragora was associated with across time. The described power of casting away demons draws a line back to Homer’s Moly, used as a protection against Circe’s magic.[2] Yet this Middle-Eastern Mandragora has two outstanding features: it glows in the dark and is elevated from its earthly home with the help of a dog. Yet the capacity to glow at night isn’t particular to Middle-Eastern tales only, the Greeks knew of a plant shining in the dark too.[1]

The glowing plant material of Greek traditions grows in the mountains and was used as a treatment for epilepsy.[1] Demons were believed to cause the uncontrollable shaking occurring as a result of an epileptic seizure; those suffering from epilepsy were therefore considered to be possessed. The shining ‘baaras’ and the gleaming Greek root both follow a trajectory against demonic powers. But despite being associated with the Mandragora, neither of them were one. Instead, both are believed to be a Paeonia officinalis, a common peony. [1]

Yet despite not ending up in the Alraunglaube as the Brothers Grimm describe it, the supposed glow emitted by the Mandragora comes up time and time again in tales told of the plant. In some, the light is recalled to only emanate from its berries; in others it is the whole plant that allegedly shines.[4] Even though there is no evidence of light cast by the Mandragora, or the peony for that matter, many tried to find answers for the curious element of storytelling.

The 12th century Arab physician and botanist Ibn al-Baytar believes nearby phosphorescing rotting wood could be the reason for the illusion.[1] Others make a substance within the Mandragora the cause of the light; so for example β-methylesculetin contained in the Mandragora’s fruits.[4] Given the right weather conditions, there is a possibility of chemical particles of β-methylesculetin escaping, which could potentially cast the plant’s berries in a faint glow. [4] Yet none of these two theories are proven to be true.

An utterly different, much more straightforward phenomenon, far removed from rotting wood or chemical substances, might however be the simple explanation for the Mandragora’s mythical light emission. Rather than the plant glowing on its own accord, it is another creature casting it while practically also creating the illusion of the plant’s shifting locations: fireflies. According to the German theologian and historian Hugo Rahner, the often-described ‘glow’ is nothing but a ‘magical reinterpretation of an utterly natural phenomena’.[4]

Gayōmart and the rhubarb

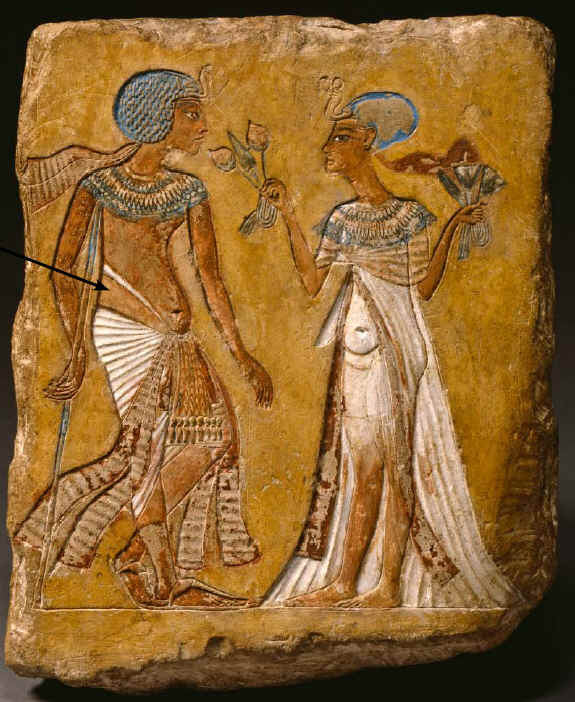

But the legacy of the Mandragora reaches much further back than Ancient Greece or Middle Eastern times. According to Ancient Egyptian myths the goddess Hathor, set on destructing all humanity, was tamed by Mandragora beer and subsequently transformed into the goddess of love, dance and joy. The bespoke beer became the most prominent sacrificial offering to the goddess thereon after. [4] So prevalent was the plant in Egyptian culture it was not only often depicted in images of its gardens, but Pharaoh Tutankhamen (1339BC) was buried with a collar of glass pearls, dried flowers, leaves and Mandragora berries. [4] Yet even the Ancient Egyptians appear to be modern in the eyes of those who were before; in the eyes of those who believed in plant-human hybrids much earlier than any stone for any Greek temple could have been quarried.

The Mandragora’s history is crowded with half-human-half-plant creatures. They appear everywhere the Mandragora goes, in stories, botanical descriptions and depictions alike: scraggily naked figures balancing opulent leafy heads ordained with long slender leaves and voluptuous berries. Yet stories of human-plant creatures are far from frequent in Europe, in fact the only existing ones are those ranking around the Mandragora. They are however numerous in Middle Eastern traditions, issuing the assumption the origin of the plant-humans must be found further east – in stories like the one of Gayōmart. [4] Zabihollah Safa, Professor of Iranian Studies at Tehran University in the 1940s, gives a concise account of Gayōmart’s legend, according to a more than five thousand year old Middle Persian text:

‘Gayōmart Gar-shāh, King of the Mountains, was the first human Uhrmazd created from mud (…). He was created in the form of 15-year-old boy and lived for 3000 years in peace, not eating, speaking or praying, although Gayōmart was inwardly considering to do so. After 3000 years the evil spirit Ahriman awakened and his monstrous creatures fought with the light. On the first day of spring, Ahriman leaped forth onto the earth in the form of a dragon. He started to seed death, illness, lust, thirst, hunger among all living things and disseminated throughout the world a class of evil creeping things including reptiles, insects and rodents. In the enrolling catastrophe Gavevagdāt, the primordial ox and source of all beneficent animal life, died. But Gayōmart could not be killed as his time had not yet come. He lived for 30 years thereafter and then, finally, as he died, he fell on his left side and shed his semen upon the ground. The sun fertilised his semen and 40 years later, there grew Mashya and Mashyana, the first mortal man and woman, as two rhubarb plants.’ [5]

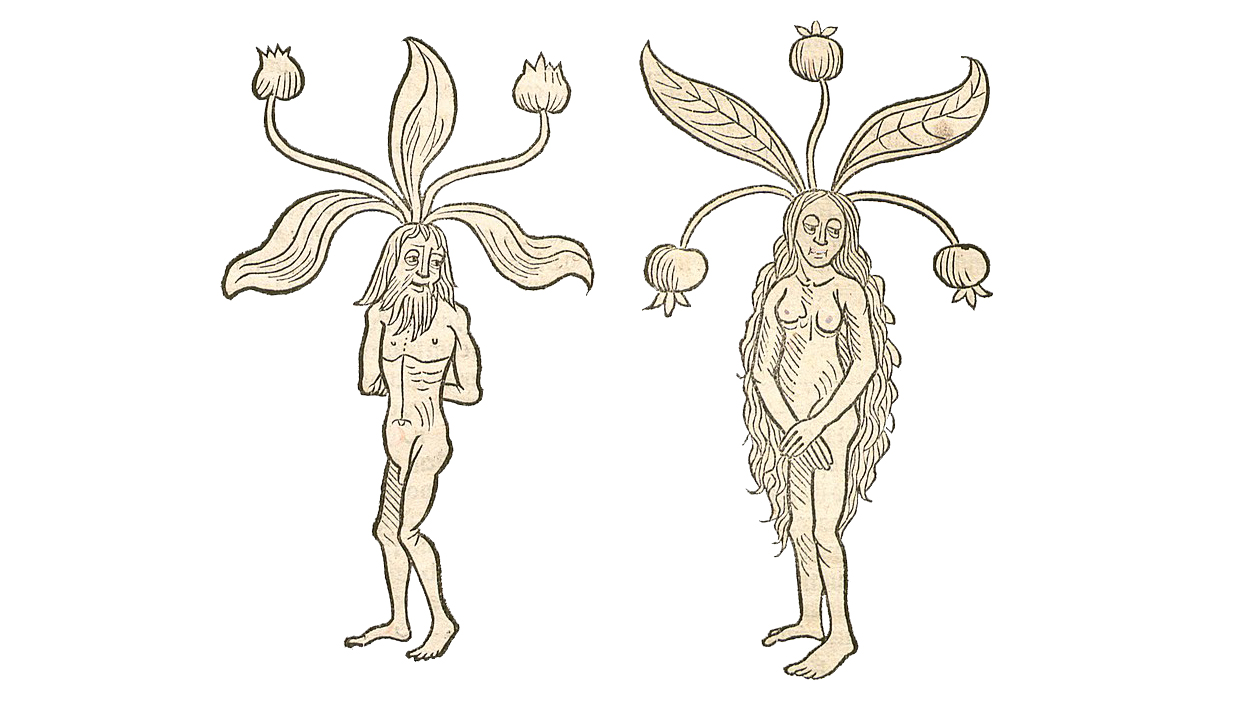

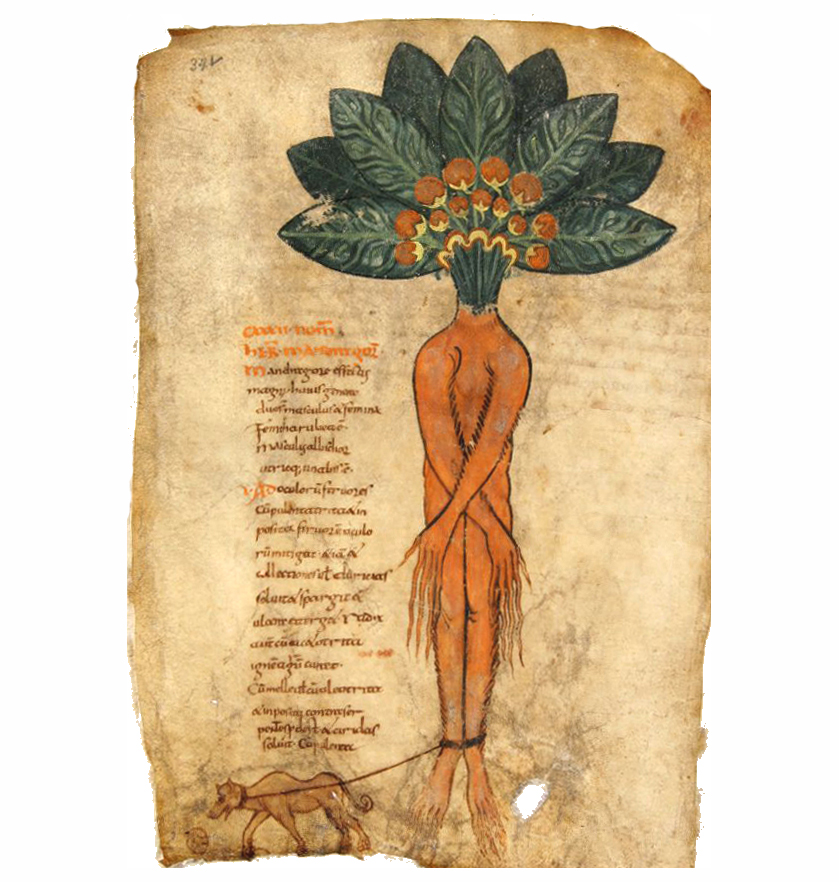

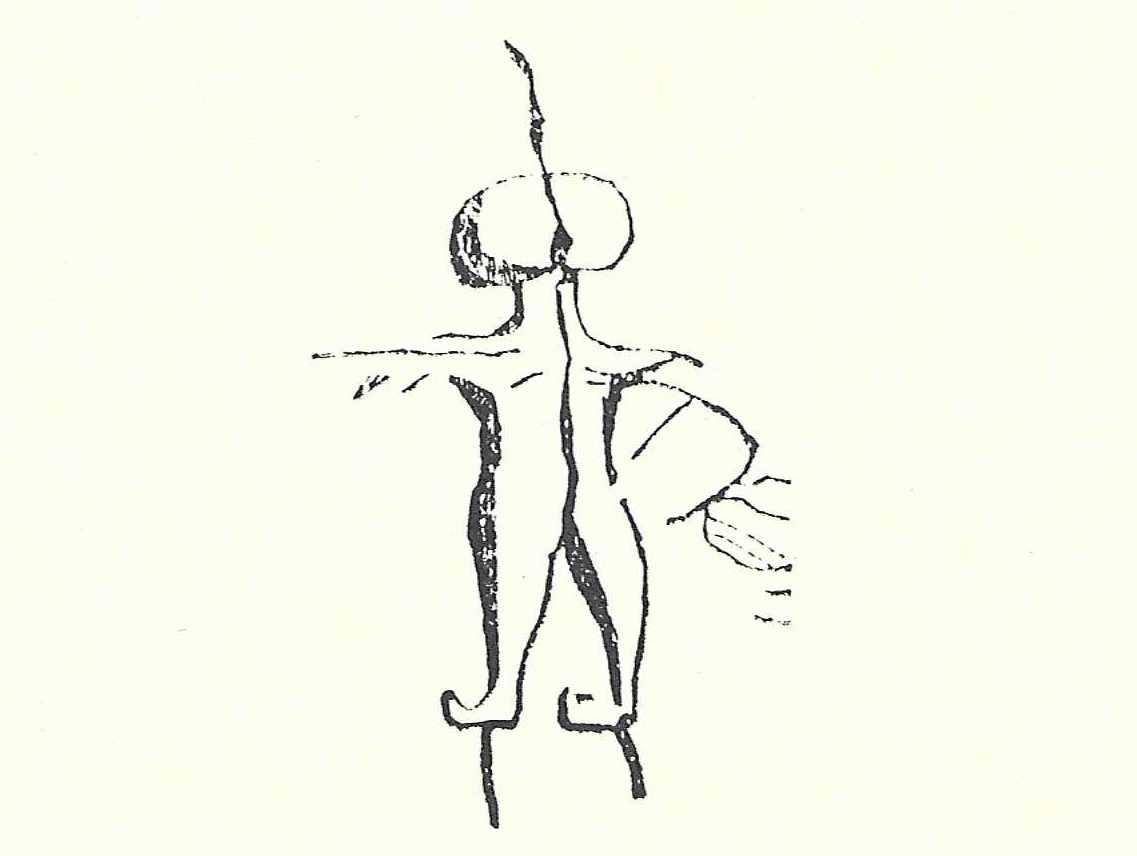

It is this Mesopotamian story that foreshadows elements of the Alraunglaube. It is this story and an unlikely plant, the rhubarb, bringing forth the last remaining elements of the story: the plant’s human shape, its gender growing both as a man and a woman, Mashya and Mashyana, and its germination from the semen of a dead man. Yet despite being of much earlier origin, human-plant creatures came to be enveloped by the Alraunglaube probably at a much later moment in time. Most likely it was only in the Middle Ages, with the growing influence of Middle-Eastern medicinal and cultural practices, that plant-humans were consumed by European traditions [2] –a phenomenon that is reflected in the growing number of Mandragoras depicted as humans from 500AD onwards.

Three plants, three stories, vastly different in times and grown on the soil of different cultural practices, were eventually digested in the Mandragora’s belly to a concoction known as the Alraunglaube. Each one of these plants have brought their own elements to the story: the deadly nightshade the uprooting rites including swords, circles and love incantations; the peony dogs and extinctions of demons; and the rhubarb the Mandragora’s propagation from the semen of a dead man, its genders and human form – a human form that was not one but came to be two, male and female.

This text is an excerpt of the piece ‘Three Becomes Two Becomes One Becomes None’ written as part of the CAS course in Ethnobotany and Ethnomedicine in 2022.

Bibliography

[1] Taylor Starck, A. (1987). Der Alraun – Ein Betrag zur Pflanzensagenkunde. Berlin: Express Edition GmbH.

[2] Wittlin, D. (1999). Mandragora. Eine Arzneipflanze in Antike, Mittelalter und Neuzeit (PhD). Universität Basel.

[3] Rätsch, C. (2021). Hexenmedizin – das Vermächtnis der Hekate. In Hexenmedizin (15th ed., p. 95-165). Hamburg: at Verlag.

[4] Hambel, V. (2002). „Die alte Heydnische Abgöttische Fabel von der Alraun“ – Verwendung und Bedeutung der Alraune in Geschichte und Gegenwart (PhD). Universität Passau.

[5] Shaki, M. (2001). Gayōmard. Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. 10. London: Routledge.

Illustration sources

Figure 1: (N.d.) (1491) Male and Female Mandragora [Hortus Sanitas] (N.d.), (N.d.). Accessed in Kräuter, M. L. P. 48-49, image: public domain.

Figure 2: (N.d.) (14th) Tacuinum Sanitatis Mandrake Dog [Drawing – Tacuinum Sanitatis]. (N.d.), (N.d.). Accessed: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tacuinum_Sanitatis_Mandrake_Dog.jpg , image: public domain

Figure 3: (N.d.) (9th) Abbildung der Mandragora [Manuscript]. Pseudo Apuleius, Kassel. Accessed at https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alraune_(Kulturgeschichte)#/media/Datei:Pseudo_Apuleius_Kassel_Mandragora.jpg , image: public domain.

Figure 4: Assyrians. (2000BC) Mandrake Root [Ancient Rock Carving]. Les Monuments de la Ptérie, Egypt. Drawing scanned from Thompson, C.J.S. (P.46)

Thompson, C. (1968). The Mystic Mandrake. New York: University Books.

Figure 5: (N.d.) (2000BC) Merit-Aton gives her husband Smenchkare a mandrake as a sign of love, 8. dynasty. Mandragora flowers and Papaver somniferum capsules depicted on ancient friezes [Ancient Frieze]. Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Berlin. Accessed at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mandragora-flowers-and-Papaver-somniferum-capsules-depicted-on-ancient-friezes-Egyptian-Museum-of-Berlin.jpg , image: public domain.