There is no doubt that 2019 will be known for decades as the “Year of Greek Grammars” in the English-speaking world. In March, the Cambridge Grammar of Classical Greek by Evert van Emde Boas, Albert Rijksbaron, Luuk Huitink, and Mathieu de Bakker appeared. In the preface, the authors make it quite clear that they regard this publication to be quite a major achievement, with Smyth’s (a century old, even in its latest revision having appeared over seventy years ago) grammar being “the last good full-scale reference grammar in English” (CGCG p. xxxi): “[It] stemmed from a time long before such [linguistic] advances had even been possible, and more recent grammar books had done nothing to bridge the gap.”

Then, in April, Cambridge University Press published yet another very much anticipated grammar, the Cambridge Grammar of Medieval and Early Modern Greek by David Holton, Geoffrey Horrocks, Marjolijne Janssen, Tina Lendari, Io Manolessou, Notis Toufexis – a work that is unfortunately as expensive as it is massive.

Some readers have expressed disappointment that the authors of both grammars decided not to discuss developments of (early and late) Koine Greek developments.

However, a new grammar – this time published in Oxford (by Peter Lang) – that has just been released now covers some of this ground.

There is also a “new edition” of Moulton’s Grammar of New Testament Greek with updates by Stanley E. Porter for each volume. I haven’t had a chance to take a look at it yet and don’t know whether this publication has the potential to join the ranks of this list …

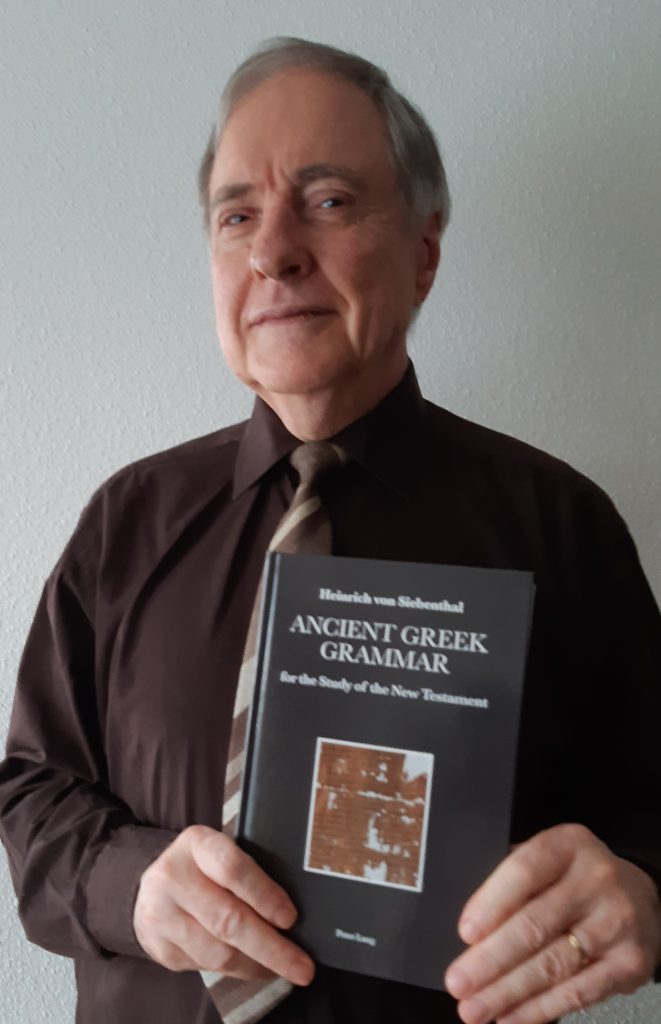

I am talking about the Ancient Greek Grammar for the Study of the New Testament by Heinrich von Siebenthal. The AGG is the translation of the German Griechische Grammatik zum Neuen Testament (GGNT) that appeared in 2011 (and is itself a thorough revision of the 1985 grammar co-written by Hoffmann and von Siebenthal).

While in the English-speaking world, BDF (Blass-Debrunner-Funk) now has been the standard reference grammar for NT scholars, their German colleagues have long had in GGNT a work that was linguistically clearly superior to BDR (Blass-Debrunner-Rehkopf). Personally – having studied Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic under von Siebenthal and having benefitted immensely from GGNT – I am very excited that this work is now also available in English. To be sure, BDF/BDR still has its value, not least (together with the linguistic key produced by von Siebenthal and Haubeck) as a scriptural index, that gives a first clue about which grammatical topic is of relevance for the passage in question (and offers some explanations for why interpretations in commentaries might differ). There is however no doubt in my mind that von Siebenthal’s AGG is the best place to go to get an up-to-date and reliable assessment (that is presented in still rather traditional – and thus also for students accessible – grammatical categories). If you do any work on NT texts (or any other texts written in Koine for that matter; it’s not a “NT grammar”), you need to get this book!

To give you some idea about the scope and shape of this project, I asked Heinrich von Siebenthal to answer some questions that I thought some of you might have:

Students

and scholars of the NT already have a variety of grammars to choose from – how

is your grammar different from the existing ones? How does it fit into this

spectrum?

HvS: I think, there are three major distinctives that set the “Ancient

Greek Grammar for the Study of the New Testament” apart more or less clearly

from other grammars:

1) It is not a text-book, but a reference grammar that systematically

covers all areas relevant to well-founded text interpretation including textgrammar

and word formation.

2) The information it provides is based on the best of traditional and

more recent research in the study of Ancient Greek and linguistic

communication.

3) The mode of presentation is largely shaped by the needs of prospective

users, typically unacquainted with the details of linguistic research or with classical

philology:

(a) Every Greek, Latin or other non-English expression is translated into

English.

(b) Knowledge of Classical Greek is not presupposed (as it is in

Blass-Debrunner-Funk); differences between classical and non-classical usage,

however, are regularly indicated.

(c) It is primarily about the grammatical phenomena of Ancient Greek (mainly

those of New Testament Greek, but also about many of the ones attested in the

Septuagint and extra-biblical texts, especially classical ones). At the same

time great care has been taken to point out what linguistic phenomena of

English correspond to these phenomena functionally and what may be considered

adequate translational equivalents.

In summary, this grammar is meant to be 1) more comprehensive, 2) more

up-to-date, 3) more

accessible than some, perhaps than most of its alternatives.

Aiming at both professional quality of content and user-friendly presentation a

tool was produced that would hopefully be of service to beginning students and

more experienced exegetes alike.

Can

you tell us a little bit about how your own education and previous research

forms the background of this publication?

HvS: Motivated by a special interest in the mechanics of linguistic

communication and in a truly scholarly approach to ancient texts, especially

biblical ones, I studied Ancient Greek, Hebrew, and English linguistics at the

Universities of Zürich and Liverpool. My time in Zürich was a major contributing

factor to me eventually producing this grammar, due mainly to the profound

influence two of my teachers have had on me: 1) Ernst Risch, an

Indo-European scholar of international renown (with a special emphasis on

Ancient Greek linguistics): He helped me find a truly scholarly approach to

Ancient Greek grammar and texts. He also kindly critiqued the earliest (German)

version of the grammar co-authored with Ernst Hoffmann resulting in a considerable

number of improvements, not least in the core parts of syntax. 2) Ernst

Leisi, a leading authority in the study of English linguistics (known

especially for his pioneering work in lexical semantics): He greatly impressed

me with the professional way he handled the complexities of linguistic

communication and the straightforward and accessible way he talked about these.

These scholars, especially Leisi, have been a constant source of inspiration to

me over the years as I worked as a lecturer on Biblical languages, particularly

so in my research, which began with my doctoral work on Hebrew synonymics to be

followed by research and publication activities focused on applying solid

findings of modern English and German as well as general (typologically based)

linguistics to Ancient Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, with an increasing interest in

text-level phenomena, always keeping in view the needs of non-specialists. It

was basically in this context that I came to produce both the German and the

English versions of “my” grammar.

In

preparing the English version of your grammar, which areas required the most

modification due to the new target language?

HvS: Case forms and their

syntax so prominent in Ancient Greek (and German) called for special attention,

of course, as in Modern English case forms hardly occur at all. Dealing

with grammatical genders required special care, too, as Ancient Greek and German,

unlike English, do not connect these with natural genders in any systematic

way. Another area, as you would expect, was the syntax of verbs forms; this

proved to be the most important and the most challenging one calling for

extensive modifications, as this is an area marked by significant differences,

in many cases very subtle ones, between Ancient Greek and English, differences

that are not the same as those between Ancient Greek and German. The use of the

perfect (indicative) is a case in point: There is some overlap with the English

present perfect, but only in cases where the “action” does not continue into

the present (“non-continuative perfect”), but where a continuing result is

indicated (“resultative perfect”), e.g. in Acts 21:28 κεκοίνωκεν τὸν ἅγιον τόπον τοῦτον He has

defiled this holy place (the defiling activity does

not continue, but a continuing result is indicated). In other cases, the

Ancient Greek perfect (indicative) does not agree in use with the English present

perfect. Interestingly, the English (continuative) present perfect is sometimes

an adequate translation of the Ancient Greek present indicative (e.g. John

14:9). Other subtle, but important differences are about the use of aspects and

moods.

Were

there any areas where you felt compelled to make changes to the substance of

your analysis due to more recent research into Greek grammar?

HvS: The changes I felt

compelled to make did not really affect my work in any substantial way. However,

I tried to offer a more consistent and thus more helpful analysis of

syntactical matters inter alia by 1) adopting a phrase-based approach to

the syntax of words, 2) more carefully defining the aspects (the volume by

Runge-Fresch proving to be important), and 3) introducing the concept of

modality (important for building a meaningful bridge between Ancient Greek

moods and the use of English modal verbs).

Morphology

and syntax make up for the biggest part of your book. However, you’ve also

added a quite substantial discussion of “textgrammar.” Could you

explain in a few sentences why you did this and what it is all about?

HvS: “My” grammar is to help

theologians and others interested in text interpretation explain in a reasoned

way what Ancient Greek texts, especially those of the New Testament,

communicate linguistically. Now, as is widely believed among today’s linguists,

linguistic communication operates by means of texts of diverse types

(invitations, requests, inquiries, offers, complaints, protests, appeals, birth

and marriage announcements, death notices, anecdotes etc.). And a text is more

than the sum of its sentences or clauses. These must be connected in a particular

way, having both a formal and content structure that enables hearers or readers

to understand what the producer of the text intends to communicate, i.e. what

content he or she means to convey and what objectives he or she is trying to

achieve. The textgrammar section is to show 1) ways in which a text is

different from the sum of its sentences or clauses and 2) ways in which

the distinctive features of the formal and the content structures of texts relate

to the communicative force (coherence) of texts contained in the Greek New

Testament.

When reading exegetical works by NT scholars, which areas of inquiry or specific question seem to be in most need of an updated grammatical state of knowledge? What do you miss the most? What would you wish NT scholars would take more into account?

HvS: I think, the text level matters I have just hinted at should definitely be taken more seriously. Words, phrases and sentences shouldn’t be looked at in isolation, but first of all as part of the text they belong to. Our primary concern should be to determine in a reasoned way what function these most likely have within the text itself, what they contribute informationally to the overall message of the text. This will necessarily lead us to that continual change between the two processes, termed “bottom-up” and “top-down”. To my mind this concern should have priority over other concerns such as the ones for connections with other texts (contemporary or non-contemporary in Greek or in other languages), though this, too, has a legitimate, but definitely secondary role to play in the process of text interpretation. Finally, let me mention one personal wish I have concerning New Testament text interpretation: Not only should we interpret these texts in a solidly reasoned way, it would be good if we were also as committed to taking their message seriously.

Christoph Heilig is the author of Hidden Criticism? (Fortress, 2017) and Paul’s Triumph (Peeters, 2017).

Christoph Heilig is the author of Hidden Criticism? (Fortress, 2017) and Paul’s Triumph (Peeters, 2017).

This research has recently received the Mercator Award in the Humanities and Social Sciences.

Additionally, he has co-edited (with J. Thomas Hewitt and Michael F. Bird) God and the Faithfulness of Paul: A Critical Examination of the Pauline Theology of N. T. Wright (Fortress, 2017).

In his most recent – and voluminous – project, which has just been completed, he discusses the importance of “stories” and “narrative substructures” for understanding Paul’s letters. It is currently in press with de Gruyter.

3 Kommentare vorhanden

1 Biblical Studies Carnival #167: December 2019 – Scribes of the Kingdom // Jan 1, 2020 at 22:45

[…] A new New Testament Greek grammar has arrived. Author Heinrich von Siebenthal discusses his approach at the Zürich New Testament Blog: Ancient Greek Grammar for the Study of the New Testament. […]

2 Ancient Greek Grammar for the Study of the New Testament (von Siebenthal, 2019) | Didier Fontaine // Mar 21, 2020 at 16:02

[…] consulter : reviews de cet ouvrage par Niedergall | Heilig | et pour l’édition allemande […]

3 Observations from a Linguistic Spectator: An Annual Report // Apr 19, 2020 at 0:01

[…] referring to the time of speaking and that it communicated the “resultative” aspect (cf. AGG 200). But I don’t think I activated that knowledge a lot during translation. I think I […]

Kommentar schreiben