2. February 2017 |

Christoph Heilig |

4 Kommentare

At the event, with a sign on the podium that read “TRUMP” and “Make America Great Again,” Mike Huckabee and Rick Santorum entered to play second fiddle to Trump’s well tuned music. They met their Zod and kneeled. Doing so, to both men, may be no big deal or may be more media exposure. But it actually declares the ends of their campaigns days before the Iowa caucuses. They were subservient to Donald Trump, not equals. Their names did not appear on the podium, only Trump’s. The crowd was not there to see these men. The crowd was there to see Trump. Like conquered kings paraded in a Triumph through the streets of Rome, Santorum and Huckabee were paraded through Drake University, now the vassals of Donald Trump.

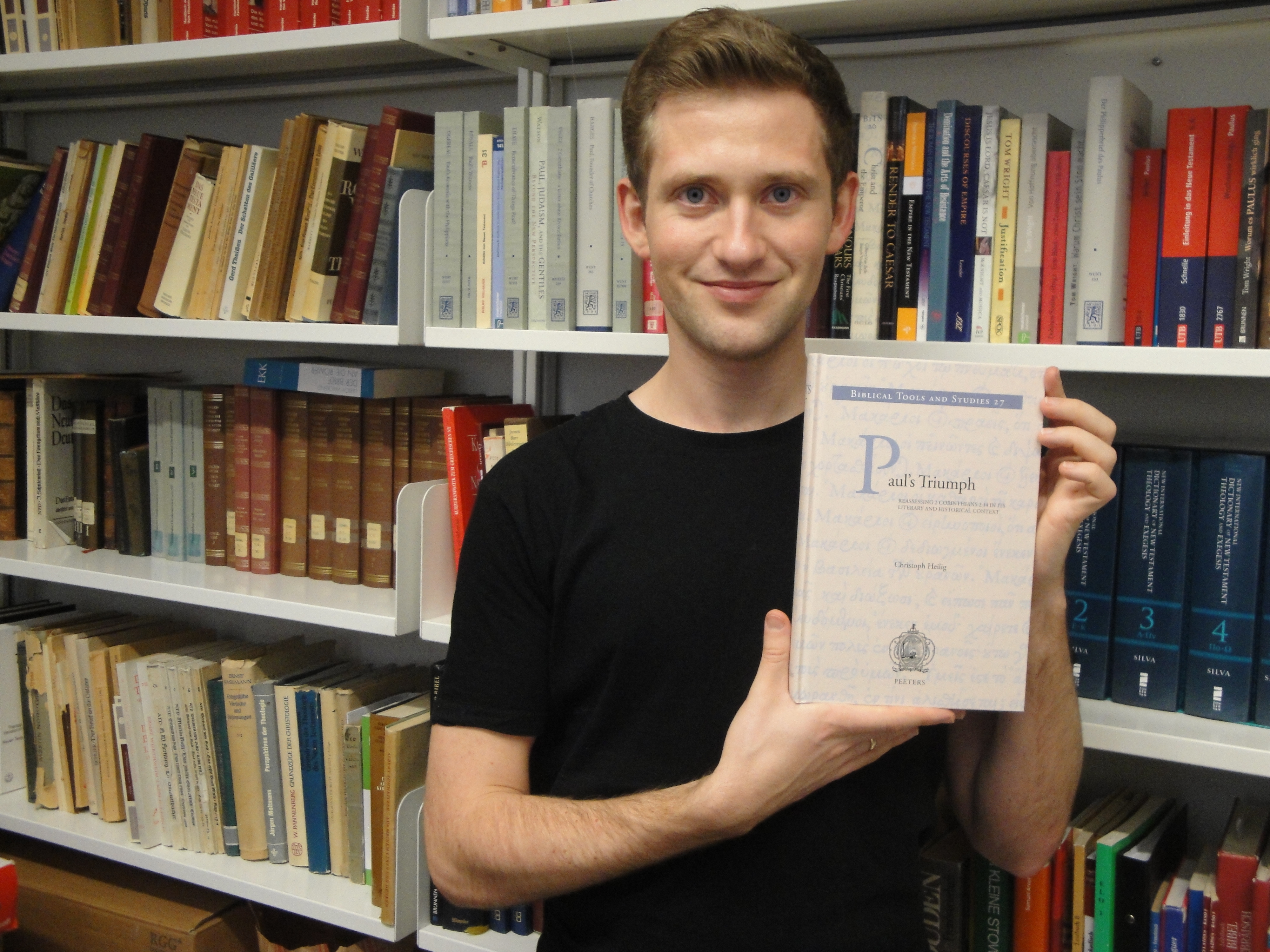

When I decided, almost exactly one year ago, to place this quote at the beginning of the first chapter of my manuscript, this was a rather risky decision – for it was a real possibility that at the time my book would appear in print, the political figure Donald Trump might already be forgotten.

(AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

As it turns out, this is not the case and my illustration – that triumphal imagery can be used in a rhetorically forceful way – remains valid and intelligible. It’s not the first time, to be sure, that such language has been adopted to make a point…

In his second (canonical) letter to the Corinthians, Paul makes an assertion about his and his co-workers that has led to quite different, even opposing, translations and interpretations: When thanking God, the one who is πάντοτε θριαμβεύοντι ἡμᾶς ἐν τῷ Χριστῷ (2:14), does he imagine himself as a victorious general (“thanks be to God, who always gives us victory/leads us as his soldiers in triumphal procession”) or as a captive who is led to execution? Or does the imagery have nothing nothing to do with the Roman military at all?

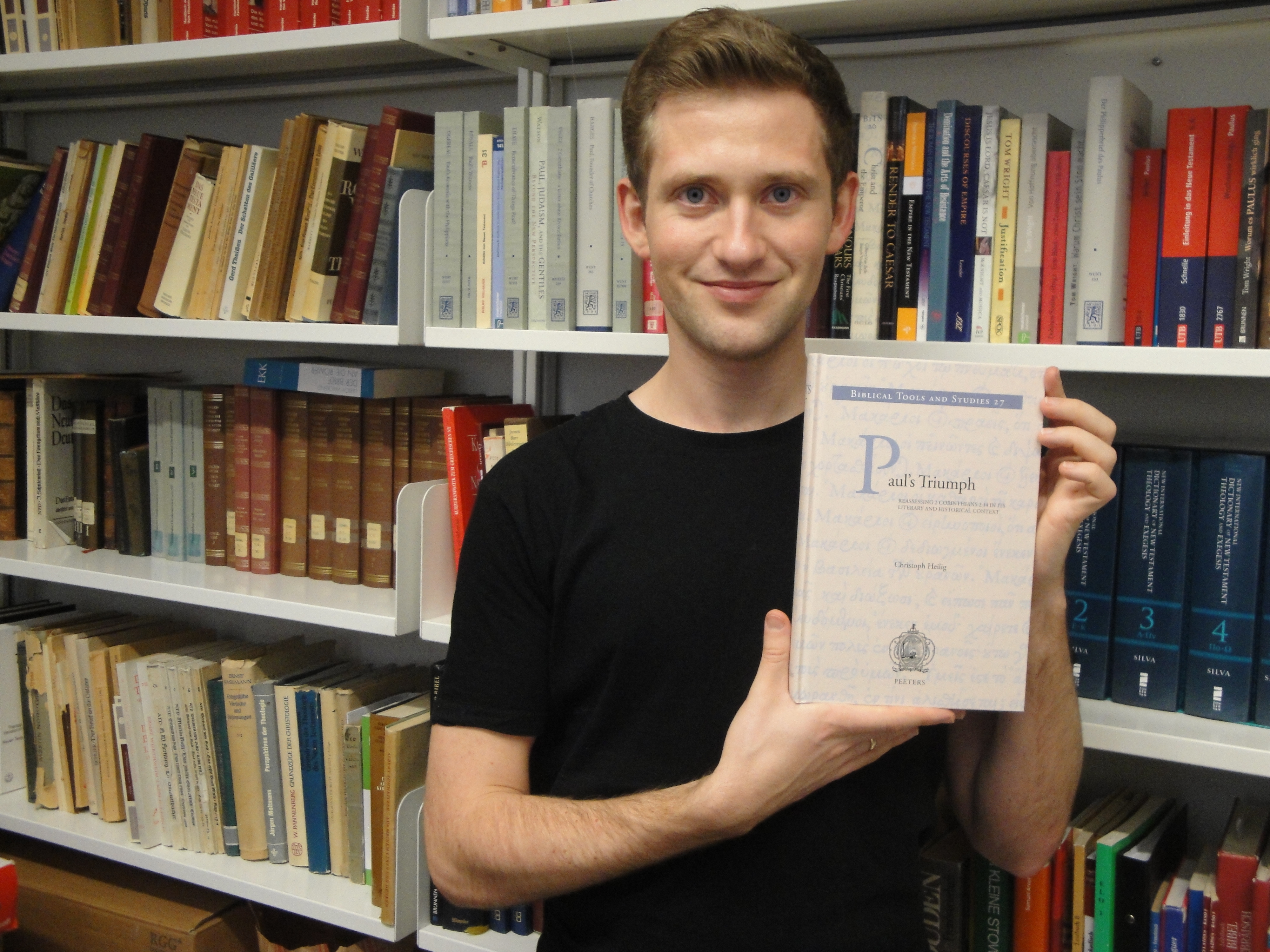

Peeters recently published a monograph – with the title Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context – that deals with these questions in detail. You can order it from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, and Amazon.de. The Table of Contents can be downloaded for free here.

In this post I would like to highlight some specific aspects of my book where I hope that I have made helpful contributions. In other words, instead of offering a summary of my argument, I would like to point out some areas (some obvious and explicitly addressed in the book, some not; some central to my thesis, others only implications it might be valuable to draw out) in relation to which the results of my research might be relevant. Of course, whether these aspects actually would profit from my perspective is for others to judge, but I would like at least to point out where I myself see some potential.

1. Paul and Empire

In Hidden Criticism? (preface and TOC can be downloaded here) I discussed the general plausibility of the hypothesis that we might find something like a counter-imperial subtext in the letters of Paul. I concluded that the hypothesis is not as problematic as some (most notably John Barclay in a magisterial essay) had argued. At the same time I suggested that for this paradigm to be heuristically fruitful, it would need to be modified in some regards. For example, I was not convinced that the attempt to avoid persecution was a plausible reason for the “hiding” or “coding” of criticism. Furthermore, I drew attention to the fact that counter-imperial resonances had to be related in a careful manner to more central communicative aims of the author.

In many ways, Paul’s Triumph is a book on its own and not simply the “application” of my theoretical thoughts from Hidden Criticism. Firstly, I was not actually concerned with offering a catalogue of criteria for identifying “echoes of Caesar” in that earlier book, but mostly with the presuppositions of this approach itself. These consideration cannot strictly speaking be “applied” but rather form the background against which, in my personal opinion, specific textual analyses ought to be carried out. Secondly, Paul’s Triumph is not simply the sequel of Hidden Criticism since it deals with much more than with the implications of 2 Cor 2:14 for Paul’s interaction with imperial ideology. (That is a “continuation” of Hidden Criticism in the strict sense only in so far as the new book picks up the concern I had expressed in that earlier publication, according to which a focus on the counter-imperial dimension alone would be prone to misinterpreting Pauline texts.) That being said, I think that 2 Cor 2:14 can contribute a lot to the “Paul and Empire” debate. Since there is not space for a detailed discussion, I will simply flag up some of the key issues here:

- Second Corinthians 2:14 is almost never used as a test case by those involved in this debate.

- Still, it can be argued that this is the one place in the Corpus Paulinum (including Phil 4:22!) that contains the clearest reference to the person of the Roman Emperor!

- The fact that Paul thinks the imagery is fitting for describing God’s action implies that we should be careful in speaking about Paul’s perception of the validity of Roman power too one-dimensionally.

- Most commentaries on Second Corinthians talk about the Roman triumph as if it was a regular event with which every citizen in the Roman Empire would have been familiar. However, they regularly miss the fact that there was only one triumphal procession by a Caesar during Paul’s lifetime …

- … and it is even possible to make a good argument that Paul met eyewitnesses of that event in Corinth!

- Thus, when Paul decides to use precisely this imagery to make his point (on this “point,” the function within Second Corinthians, cf. below on coherence and literary unity), he most likely picks up a conversation that he had previously had in Corinth on this very topic.

- Therefore, instead of assuming that Paul is simply using a kind of general, shared cultural knowledge, we should rather assume that he has a very specific triumphal procession in mind as a negative foil to the one he is describing.

- Hence, Paul’s talk about his role in God’s triumphal procession should be taken seriously (besides the other things it is) as one of the few surviving takes on this specific event.

- Furthermore, it should be noted that, following from this, the “counter-imperial” potential of the passage does not reside in a categorical statement about the Roman Empire as such, but rather in the specific contribution to an issue of “contemporary politics.”

If you are interested in the broader topic of Paul and Empire, this recent blog post on Bruce Winter’s contribution to this debate might also be of interest for you.

2. The Methodology of Exegesis

Many students of the New Testament learn exegesis with the help of a textbook that suggests that they follow certain “steps” in order to write a paper on the meaning of a certain passage. Some of these books do a great job in summarizing tools that have been demonstrated to be valuable in exegetical research (if you are interested in such things, make sure you check out this recent innovative German textbook, which for some reason does not yet seem available on Amazon). However, there are several problems with such a pedagogical approach that are not easily overcome:

First, it is almost impossible for textbooks to do justice to the diachronic character of the development of the methods they suggest. Therefore, students often are more confused rather than enlightened after reading the relevant chapter on, to give just one example, “form criticism” (which is “Gattungskritik” in German, while we have, of course, also “Formen” – just to make the confusion even worse), which builds on rather disparate versions of an approach that is connected above all by similar terminology. Without being familiar with the older German research on the “Sitz im Leben” of Old Testament texts and on Bultmann’s hypotheses on the formation of the Synoptic Gospels, it is almost impossible to understand how different accounts of form criticism relate to each other.

Second, even if students are able to actually understand and implement the individual steps of the exegetical “procedure,” there is the danger that because they have that recipe or formula, they lose sight of the very nature of what they are doing: What does it mean to do exegesis? What is the task at hand? It is important that we do not only know how we get there, but also exactly why these steps lead us to the goal we want to reach. It is important for the reason that only if we understand the basic inferential structure of what we do that we can really evaluate and interact with arguments by other scholars. How, for example, are we supposed to combine the results assebled through different methods so that each bit of evidence receives the appropriate significance?

This kind of textbook-exegesis, so to speak a “step model” of exegesis (in which the goal is reached by working through a series of individual tasks and adding the results on equal terms), is not limited to student papers, to be sure. To be fair, it should be noted that there are certain advantages associated with that approach, such as the fact that in such a framework evidence of all kind is assembled and the reader can decide for him- or herself, whether he or she agrees with the conclusion that is reached or whether he or she would weigh evidence differently. Still, I would maintain that problematic consequences are noteworthy as well. Let me just give one example. Recent years have seen an explosion in the publication of commentaries, for obvious (not necessarily unethical!) reasons: they sell well (which makes the publisher happy) and depending on the format they can be written in a rather short amount of time, e.g. because the author can use his or her lecture notes (which makes the author happy). It is by no means my intention here to criticize every aspect of that trend (I recently co-translated a commentary myself!), but the recent debate surrounding plagiarism seems at least to have demonstrated, that there is a certain danger for some standards of good academic writing. Similarly, this also affects the way exegetical decisions are reached in many (though of course not all!) commentaries. While working through ca. 100 commentaries on Second Corinthians, from the 18th to the 21st century, I noticed a staggering amount of problematic issues: mistaken references to primary sources that were copied without checking them, references to different positions by different authors as if they were supported equally by the evidence although they clearly were not, decisions for one of the semantic options on the basis of an aspect that can actually count as a minor step on the actual inferential path to a well-substantiated result, etc. I plan to write on the history of research on that passage somewhere else, but I note this here because I would like to point out that sometimes the exegesis in commentaries suffers from a similar deficiency as some student papers: some authors follow a rather eclectic approach of collecting and evaluating arguments in the literature, because they do not seem to be aware of the inferential structures that should underlie their conclusions. In the book I adduce some examples, in order to draw attention to the importance of the aspect of methodology.

Together with Theresa Heilig, I’ve written an extensive introduction to abductive and Bayesian reasoning and I do not want to repeat these considerations here. What I would like to point out is the fact that Paul’s Triumph explicitly follows the structure of an inference as supported by considerations from confirmation theory in evaluating the relevant evidence. Therefore, my book can also be read as an argument for the value of epistemological considerations for exegetical practice. Getting in new primary evidence is key (cf. the forcefully argued case by Jörg Frey in the introductory essay of his recent volume), but having established a methodologically sound framework first, in which we can then fill in the data, is nevertheless obligatory. For those who are skeptical towards the additional value contributed by such considerations, my book might thus be an interesting test case. As I think I have demonstrated in Paul’s Triumph, many of the innovative proposals in the literature look very convincing at first sight only because they follow an inadequate inferential structure. If scrutinized within a methodologically complete framework, it becomes clear, however, that their plausibility is actually quite, sometimes even extremely, low.

3. Lexicography

Inasmuch as I take a look at the ancient usage of the Greek verb θριαμβεύω (used in 2 Cor 2:14 and in Col 2:15), my book aims at contributing, rather obviously, to the field of lexicography. I mention this explicitly, however, because I think that an important and by no means trivial implication of this research could lie in illustrating just how much effort it takes to determine the semantic range of a particular Greek word. Most NT scholars will certainly be aware of this, but I think it is a valuable reminder of the fact that the production of a really good lexicon is incredibly difficult.

Vice versa, this means that most dictionaries we use are rather limited with regard to how well supported the semantic information they provide actually is. I highly recommend John Lee’s historical analysis, which demonstrates that modern dictionaries often simply rely on information assembled hundreds of years ago. Indeed, it is not infrequent that they simply transliterate the transmitted Latin glosses. When I wrote a rather critical review of the NIDNTTE some time ago, this was not because I did not think that the editor was qualified (I profited immensely from Silva’s introduction to lexical semantics!), but because it seemed simply impossible to me that anybody, not even an expert like Silva, could perform such a task on his or her own.

The precise reason that it requires so much time to substantiate a meaningful definition of a Greek (or English!) word, is that lexemes have meaning only with respect to how they are used in relation to other expressions in that language system. In order to speak in a meaningful way about θριαμβεύω, it is thus absolutely necessary to see how it is used differently in comparison to, for example, νικάω.

Therefore, I would be very glad if my book would have the effect of encouraging students of the NT to consult not only their dictionaries, but also to familiarize themselves with the Online TLG Corpus, which is a great resource that can help us in cases where dictionaries cannot solve our problems (because often they only offer a gloss and we do not know whether a certain aspect is also included in the Greek equivalent, etc.).

4. “Word Studies”

When we talk about “word studies,” we are dealing with a phenomenon that enjoys a certain popularity in more popular books or in sermons: the author or the pastor aims at shedding light on a particular passage by telling us what else it can mean in many different places (even though, in these places this “meaning” regularly is something that emerges only because of contextual factors) – or he or she wants to point out the particular emphasis of a biblical author by contrasting the usage with meanings chosen in other biblical (or non-biblical) writings. In biblical scholarship, this notion has (for these reasons, most notably put forward by James Barr) been regarded with more skepticism in recent years – even though the problematic moves Barr had identified have certainly not been erased from academic publications yet. (Cf. on this whole topic my discussion of the TWNT/TDNT, the TBLNTs/NIDNTT, and the NIDNTTE.)

I adduce this area separately from “lexicography” because in this context, we are often dealing with the discourse meaning of a certain expression, i.e. with the communicative function of a particular word or phrase in a specific context. (In practice, as I just mentioned, it is often several discourse meanings that are adduced or compared.)

What connects this topic with the one discussed above is the fact that (usually but not exclusively) on a less academic level this discourse meaning is regularly determined by (a) opening a dictionary at the relevant place and choosing the gloss at the very top of the entry on our word. There is a certain logic behind such a procedure: Assuming that the meanings that are documented most frequently for that lexeme are listed first, one is less often wrong in constantly picking that meaning compared to always choosing a less frequently existing meaning. However, even if one always picks the dominant meaning (that is, for example, the one coming to expression in 90% of the texts) in translating a single Greek sentence, one nevertheless will inevitably make a misjudgment quite soon. (If one picks a meaning along these lines only twenty times, the probability that at least one is wrong is almost 90%!)

Why is that? Authors do not first choose a word and then contemplate what meaning they want to invest it with! Rather, they begin with a certain mental concept, a content they would like to express, and they then search for a term that could serve that end. Thus, if one of several meanings of the same word is attested less frequently, this could simply be because the concept that is expressed by it does not show up that often in this particular corpus. Hence, we should be looking for a different “frequency”: How often are different words respectively used to express the same idea, in comparison to other lexical options? If an author wishes to communicate a certain proposition, he or she might plausibly use a word that is far more often used to express a different idea – simply because it is still the best available choice for that semantic content. So here again, just as with establishing a definition/definitions for a lexeme, paradigmatic relations – i.e. the place of a word in a web of semantically related expressions – is of ultimate importance. Real “word studies,” thus, do not only look at a single expression, but actually at several related words, making it a much more time-consuming and complex task, to be sure.

Another common strategy for determining the discourse meaning errs at the other side of the spectrum, namely (b) by determining the semantic content of a word or phrase on the basis of context alone, even if the author would have had much better expressions at hand (see above), presupposing for a moment that he or she had actually wanted to express that thought.

In order to determine the communicative content of an utterance it is, hence, important to take into account both the proposition that one might expect on the basis of the semantic structure of the passage as a whole (“context”) and the lexical alternatives (“paradigmatic relations”) the author would have had for expressing the respective ideas. I do not want to claim that my analysis of 2 Cor 2:14 is in anyway complete in that regard. However, it is my hope indeed that while it confirms that “word studies” cannot be achieved cheaply, they are, nevertheless, worth the cost. The valid criticism by Barr notwithstanding, they offer worthwhile research perspectives and there is still a lot we can learn about the New Testament by focusing on the “discourse meaning” of specific expressions.

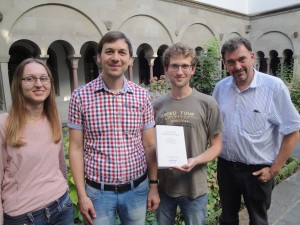

By the way – taking the opportunity to insert once again a picture into this long text – we also had a workshop on this subject a few months ago. Stay tuned for a report on our workshops from 2016 related to ancient languages!

5. Paul’s Creative Use of Language, the Coherence of Thought in Second Corinthians, and the Literary Integrity of the Letter

It is well known that in 2 Cor 2:14 the text suddenly shifts from a travel account to a praise of God, which is then followed by a lengthy discussion of the apostolic ministry – only to return again to the narrative in 7:5 (!). Hence, this transition from 2:13 to 2:14 has put itself forward as a prime example for a literary break within Pauline literature. Even though no longer as prominent as some decades ago (see for example the rather restrained position in Schnelle’s introduction to the NT), partition theories, especially within the Corinthian correspondence, are still alive.

I personally think that, first, there are good (evidence-based) reasons for having an a priori suspicion at least towards the rather complicated versions of these hypotheses (see also here) and that, second, the transition from 7:4 to 7:5 cannot be easily integrated into such a paradigm. However, when discussing my research with other scholars, I noticed that even if one were disposed towards assuming that 2:14-7:4 were a letter fragment, the analysis of the lexical semantics of θριαμβεύω should most certainly tip the scale towards assuming literary integrity. For if the verb is understood in its common ancient sense, the metaphor seems to pick up (and challenge!) the earlier notion of the chaotic travels by Paul and his co-workers. In fact, I would like to argue that Paul’s triumph imagery is a rhetorical masterpiece in that it encourages the Corinthians to identify themselves with the crowd watching such a procession, including the humiliated prisoners, “only to find themselves challenged by their simplistic perception of Paul’s ministry” (Paul’s Triumph, 259). This observation would be significant even without the guiding question concerning literary unity insofar as lexical semantics apparently help a lot in clarifying the coherence of the text on the level of content in this case and furthermore shed light on Paul’s creative use of language in general. Beyond this, however, the fact that against the background of ancient linguistic usage the choice of θριαμβεύω in 2 Cor 2:14 in its canonical position makes perfect sense is a significant argument against the hypothesis of a letter fragment.

The argument becomes even more forceful if we turn it on its head: Presupposing what we know about the meaning of θριαμβεύω, what do we think could have preceded it in the original letter? If our reconstruction of the original context looks somehow like 2 Cor 1:1-2:13, postulating such a fragment becomes obsolete …

I would even go so far to say that θριαμβεύω in 2 Cor 2:14 is a good test case for the heuristic value of Briefteilungshypothesen. True, the meaning of the lexeme is difficult to ascertain and scholars who assumed literary unity did often participate in the refusal to advance this discussion. Still, I think it is noteworthy that those who assumed a literary break often talk about the transition from 2:13 to 2:14 being rather difficult, without discussing the lexical sense of θριαμβεύω in any detail. Understandably so – for if we don’t know the originally preceding context, we have no real need and no contextual indications to establish its meaning. However, this reasoning becomes circular when the break is assumed on the basis of θριαμβεύω not “making sense” at the current position, i.e. under the assumption of a certain meaning of the word.

Not only is such reasoning circular, it also demonstrates that at least in some cases (i.e., I do not want to claim that this affects the paradigm as a whole) the assumption of a literary break is (a) premature, (b) prevents us from discovering textual coherence we would find if we took a closer look, and (c) even functions as a “science stopper” within its own boundaries insofar as it does not encourage clarifying details (such as, in this case, the semantic range of θριαμβεύω) that are more likely regarded as pressing issues on the assumption of literary unity.

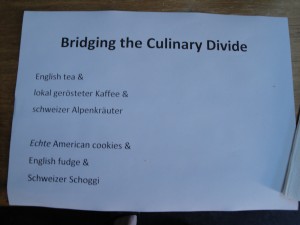

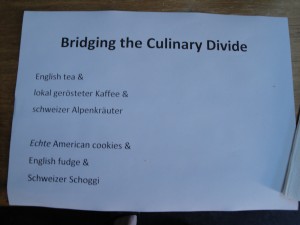

6. Bridging the German-English Divide

Lastly, I would like to point back to the very first post on this blog, where I retell how it came into existence. It was Wayne Coppins’s suggestion to create the blog in order to make our research more accessible to the English-speaking world. I won’t go into the details of the “gap” between the English- and German-speaking academic spheres here, for you can read more about Wayne’s view on this there. Here, I would only like to make some remarks regarding Paul’s Triumph with an eye on that topic.

Scott Hafemann (St Andrews) in his 1986 dissertation arguably suggested the most influential interpretation in recent times by arguing that the verb expressed the thought of Paul being led to death – with death being a metonymy for the apostolic suffering. Interestingly, it was the German-speaking scholar Ciliers Breytenbach (Berlin) who brought forward an alternative (less offensive?) interpretation a few years later (English version of the article: 1990; German version: 1991). He thought that θριαμβεύω with direct object simply expressed the celebration of a victory over the person referred to by the object – without that person necessarily being present (i.e., led [to death]) in the procession. Being followed by Jens Schröter (now his colleague in Berlin; for his English publications, see here), Breytenbach’s suggestion became quite influential in German circles, but also beyond.

Thus, we have here a very good example of an international dialogue – and of the importance of giving ear to all these voices! One of my criticisms of the NIDNTTE was that the relevant entry on θριαμβεύω did not even refer to this option suggested by Breytenbach (while the German revision accepted that interpretation but did not take note of Hafemann’s proposal!). This seemed all the more problematic to me since a few years ago a German revision of the work that the predecessor of NIDNTTE was translated from was published – relying heavily on Breytenbach’s suggestion. But even though it might be an exception these days that an English publication does not note the existence of Breytenbach’s suggestion, the same is not true for the – very few – critical reactions this suggestion has evoked. There are several shorter critiques in the English-speaking literature that are usually not adduced in German treatments of the passage and there is, more importantly, an extensive response to Breytenbach in German – Margareta Gruber’s Herrlichkeit in Schwachheit (1998) – which has almost completely escaped the awareness of English scholarship for twenty years! This is arguably the case because it was published in a lesser known series: Forschung zur Bibel. I myself had worked on the topic for a long time before finally finding this work! (Sometimes, to be sure, it does not seem to be the language barrier that keeps scholarship from being recognized … Only a few weeks before finishing my manuscript I learnt that already in the 1970ies David Park had tried to find as many occurrences of θριαμβεύω in ancient literature as possible… Still, I found his dissertation mentioned only in two or three works on the subject.)

Thus, I would like to end this post with a short and simple advice on how best to find German literature. One of the aims listed in our first blog post is to provide “discussions of important new studies that are published in lesser known series in German.” I don’t want simply to list specific German series that are regularly missed in English publications, such as Forschung zur Bibel, but rather to offer two tips with regard to a more general strategy. (1) If you are working on a specific NT text and you are looking for German (periodical) literature, it is very helpful to use online bibliographies that allow for searches on specific biblical passages (see here, here, and here). (2) In order to get your hands on recent book chapters and monographs, it is my own experience that it does not suffice simply to look up your passage in up-to-date and extensive commentaries in English (such as NIGNT or NICNT). The best way to proceed seems to be to identify a very recent German monograph that deals with the subject and to take a close look at the literature adduced in the footnotes. This might lead you to literature you might otherwise overlook for years!

In conclusion, I would like to take the opportunity of the topic of this section to reiterate my thanks to Wayne Coppins:

To Wayne, who is truly ἀξιοθριάμβευτος

[Dedication of Paul’s Triumph, p. vii]

Of those who struggled through the whole thing one person has to be singled out: Wayne Coppins once again willingly read my manuscript in a very diligent manner, helping me with countless issues relating to the English language but also giving me constant feedback on strengths and weaknesses of my argumentation. Wayne perfectly exhibits the seldom virtue of being selfless, always ready when need be without demanding anything in return. Thus it is not just on the basis of his tall stature and good looks that he is ἀξιοθριάμβευτος, making marching together in God’s triumphal procession much more fun and academia a better place.

[From the praface of Paul’s Triumph, p. x; I should note that I use ἀξιοθριάμβευτος in the sense Sueton apparently understood it as well. It has been argued that the meaning Caligula had intended is everything else but charming … cf. Paul’s Triumph, p. 197. If you wonder what might be positive about being “worth being led in triumph” (LSJ), you might want to consult 2 Cor 2:14 and a certain recent monograph on the subject … ]

Christoph Heilig is working on an SNF-Project on “Narrative-Substructures in the Letters of Paul” with Prof. Jörg Frey. He is the author of Hidden Criticism? Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul, (Mohr Siebeck, 2015) and Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context, (Peeters, 2017). Additionally, he has co-translated (with Wayne Coppins, the main translator and editor of the project) Michael Wolters The Gospel According to Luke and co-edited (with J. Thomas Hewitt and Michael F. Bird) God and the Faithfulness of Paul: A Critical Examination of the Pauline Theology of N. T. Wright (Mohr Siebeck, 2016).

Abgelegt unter: From us or people associated with us⋅ Hints to and reviews of German literature you might otherwise miss

14. January 2017 |

Monika E. Götte |

Keine Kommentare

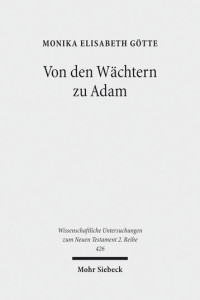

In this blog post I would like to provide a short summary of my PhD dissertation ‘Von den Wächtern zu Adam. Frühjüdische Mythen über die Ursprünge des Bösen und ihre frühchristliche Rezeption’, (From the Watchers to Adam. Early Jewish Myths on the Origins of Evil and their Early Christian Reception) which was published in Mohr Siebeck’s Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament (WUNT) II in October 2016.

In the early Jewish-Christian tradition, the question of the origin of evil is explained through the use of various mythological concepts, such as the idea of a cosmological dualism as found in the treatise on the two spirits (1QS III,13-IV,26) or the later rabbinic concept of the ‘evil inclination’ (jerobablzer ha’ra). Most prominent among these types of explanations of evil are the Enochic myth of the Watchers and the narrative of Adam’s fall. In my dissertation I analysed the development and the reception of these two motifs, revealing a gradual shift of the explanation of evil’s origins from the Watchers to Adam and, later, to the primordial fall of Satan.

Since the discovery of various fragments of 1 Enoch among the Dead Sea Scrolls, it has become possible to date the Enochic corpus (that was formerly almost only known in ge’ez) much earlier than previously suggested. Therefore, the composition of the Book of the Watchers (1 Enoch 6-36) can be moved back to the 3rd century BC. In the time from the 2nd century BC until the beginning of the 1st century AD, the tale of the ‘fallen angels’ (see also Genesis 6,1-4), their giant offspring and the evil spirits emerging from the dead giants was a widespread explanation for the evils on earth, such as violence, idolatry, and fornication. However, the narrative of the first humans in the Garden of Eden and their transgression initiated by the snake, as we find it in Genesis 3, is neither referred to as a potential explanation for evil or sin in the writings that we now find in the Hebrew Bible, nor in the writings of Early Judaism. On the contrary, the tale that has become the explanation for evil and sin on earth in Christian theology is first referred to in the context of sin and evil in Paul’s epistle to the Romans (“Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death came through sin, and so death spread to all because all have sinned…”, Romans 5,12 NRSV). Later on, for example in the Apocalypsis Mosis and the Vita Adae et Evae, the Eden narrative is connected to the idea of Satan as a fallen archangel who takes his revenge on humans by leading them to transgression.

Through the analyses of the Watcher and the Eden narrative and their respective history of reception, the following implications become apparent and are here roughly summarized: From the 1st century AD, the Genesis 3 narrative became more important, whereas the Watcher-myth lost influence. The gradual shift from the Watchers to Adam also implies a shift from human fate to human responsibility: The myth of the watchers implies (at first) no human guilt but locates the origin of evil in the ‘divine sphere’. The transgression of Adam however implies human guilt and sin as the origin of evil.

There was, despite an obvious preference for one or another conception of evil at different times and in relation to different concerns of communication, at no time a ‘master explanation’ or a ‘master narrative’ of the origin of evil. Rather, there is a plurality of explanations of evil within the biblical and the early Christian tradition that leads to hermeneutical issues: If evil is not explained in a uniform and definitive manner but is left open in a multifaceted interplay of motifs, what does this mean? First, the plurality of explanations reflects the variety and vivacity of Jewish theology and its adaptability in view of different historical and/or theological challenges. The classification of evil is therefore variable depending on situation and intention: What is interpreted as ‘evil’, be it as sin or fatal destiny, is at first due to experience and not to dogma. The rating of something as ‘evil’ is thus in a certain way arbitrary. At the same time is it exactly this plurality of interpretation that preserves the connectivity to experience.

Finally, the contextual interpretation of evil and its origins (‘what’, ‘for whom’ and ‘why’) leads to the assumption that the question of evil didn’t have to be answered unambiguously (‘dogmatic’). The answer to the question of the origin of evil is subordinated to the theological idea of the one and almighty God of Israel. Under that assumption it is clear that there can be no independent force of evil in a strongly dualistic sense (as perhaps an ‘anti-God’ or a demiurge); at the same time, still under the ‘monotheistic assumption’, there are a lot of possible varieties of divine, angelic, human, satanic, or demonic involvement in the origin of evil.

Dr. Monika Götte (*1985) wrote her PhD dissertation at UZH (University of Zurich) and is currently working as a Pastor in Stäfa (ZH).

Abgelegt unter: From us or people associated with us

20. December 2016 |

Christoph Heilig |

1 Kommentar

Given that Christmas is just around the corner, I thought that for some of you it might be interesting to get an annotated list of the books we have published this year – just in case you still need some last-minute entries for your wish list …

Frey, Jörg. Der Brief des Judas und der zweite Brief des Petrus. THKNT 15/II. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2015.

As you can see, this book was published last year already. However, since it appeared in print after the annual SBL meeting, I thought that it kind of belongs to this academic season and that it, hence, should be included in this list. This commentary is the result of one decade of research and writing by Jörg Frey and is a rather massive work, being about three times the length of the volume in that series that it replaces. You can take a look at the TOC and the daunting bibliography here. Here is the description by the publisher, which gives you a good idea of Frey’s specific contribution:

In the NT canon, the two minor »catholic« epistles of Jude and Second Peter, are often considered somewhat marginal. Scholarship has neglected them for long. The present commentary aims at demonstrating the particular achievements of the two writings without concealing the open theological questions. More precisely than before, the author elaborates the historical location of the two writings, their literary context, the profile of the respective opponents and the particular interests of the argument. The difficult text critical issues and the reception of Biblical, early Jewish and Apocalyptic material are discussed in separate sections, and a synthesis of the respective theologies of the writings is added. Jude is ultimately read as part of a critical debate with Pauline and post-Pauline developments, whereas Second Peter turns out as a testimony of theological discussions of the second century.

Heilig, Christoph, J. Thomas Hewitt, and Michael Bird, eds. God and the Faithfulness of Paul: A Critical Examination of the Pauline Theology of N. T. Wright. WUNT II 413. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

If you are interested in the scholarship of N. T. Wright or in Pauline studies in general, this collection of 30 scholars in discussion with Wright’s magnum opus is probably perfect for you. Todd Scacewater from Exegetical Tools writes that “this new book from Mohr Siebeck is a sure guide to the most contentious issues in Wright’s account of Paul’s theology” and that he “highly recommend[s] it to any students of Pauline theology and even to pastors who want to engage in rigorous Pauline debates.” He concludes by saying that “for Pauline scholars, it would be irresponsible not to own this volume!” Also, I have just seen that Andreas Köstenberger has included it in his Top 10 Biblical studies books of 2016. We are really pleased with the great interest in this book, which had been sold out after only a few months. It is now available again from Mohr Siebeck. If you don’t own it already, you can order it now here. If you would like to know more, you can check out the TOC here. Furthermore, note that we have a series on this blog on the Zurich contribution in this volume: Part 1 on Benjamin Schliesser’s analysis of Wright’s PFG in comparison to other Pauline theologies, Part 2 on Theresa Heilig’s piece on Historical Methodology, co-authored with myself, and Part 3 on Jörg Frey’s and N. T. Wright’s “apocalyptic” encounter.

Poplutz, Uta and Jörg Frey, eds. Erzählungen und Briefe im johanneischen Kreis. WUNT II 420. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Of course, Jörg Frey also has a Johannine publication this year. Here is the link to the publisher and this is the description of the volume in English (the volume contains two essays that are not in German):

The relationship between John’s Gospel and the Johannine Epistles is still disputed. The present volume combines studies directly addressing this relationship with further detailed studies on the Fourth Gospel and the Epistles of John. Apart from the question about their direct relationship, the issues of ‘docetism’ and ‘antidocetism’, the problem of the community meals and further issues of Christology, sin and sinlessness, mimesis and ethics are discussed.

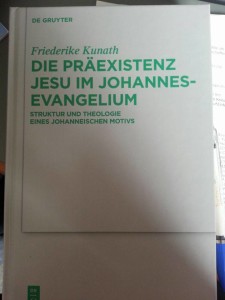

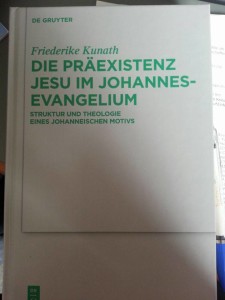

Kunath, Friederike. Die Präexistenz Jesu im Johannesevangelium: Struktur und Theologie eines johanneischen Motivs. BZNW 212. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2016.

This book, which appeared this summer, is Friederike Kunath’s dissertation, which she had completed under Jens Schröter in Berlin in 2014. It deals with the important issue of Jesus’s preexistence in the Gospel of John. Fortunately, she wrote a quite detailed summary in English for our blog, which you can find here.

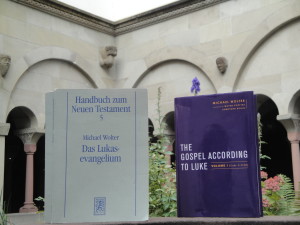

Wolter, Michael. The Gospel according to Luke: Volume I (Luke 1-9:50). Edited and introduced by Wayne Coppins and Simon Gathercole. Translated by Wayne Coppins and Christoph Heilig. Baylor-Mohr Siebeck Studies in Early Christianity 4. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2016.

Even though it might not be recognized by all as such, translation work is an important aspect of biblical scholarship. I am, hence, especially honored that this year I could assist Wayne Coppins in his important task of making German research on the NT and early Christianity more accessible to the English speaking world. You can find my own thoughts on Wolter’s commentary and our translation project here. Also, note that subsequently Wayne Coppins has also posted on this on his blog. If you are not already following his blog on Facebook, I would strongly encourage you to do so. First, it is a most excellent resource for all who are interested in German-speaking scholarship on the New Testament. Second, if you like our blog you are almost obliged to do so, given the fact that this very project was Wayne Coppins’ idea. If you haven’t already, you can learn more about that in our first blog post.

Götte, Monika. Von den Wächtern zu Adam: Frühjüdische Mythen über die Ursprünge des Bösen und ihre frühchristliche Rezeption. WUNT II 426. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

I am especially glad to include this book into my list since it is the publication of a dissertation of one of the members of our peer mentoring group. This book deals with the important issue of the origin of “evil,” both from a historical perspective and with attention to some of the hermeneutical questions associated with this foundational issue:

In the early Jewish-Christian tradition, the question as to the origin of evil is explained through the use of various mythological concepts. Most prominent are the Enochic myth of the Watchers and the narrative of Adam’s fall. Monika Elisabeth Götte analyses the development and the reception of these two motifs, revealing a gradual shift of the explanation of evil’s origins from the Watchers to Adam and, later, to the primordial fall of Satan. The plurality of explanations within the biblical and the early Christian tradition leads to hermeneutical issues: If evil is not explained in a uniform and definitive manner, but is left open in a multifaceted play of motifs, what does this mean for Christian theology?

You can get it here.

Frey, Jörg. Von Jesus zur neutestamentlichen Theologie: Kleine Schriften II. Edited by Benjamin Schliesser. WUNT 368. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

This is a publication you shouldn’t miss! As you might know, there is a collection of Jörg Frey’s essays on John, Die Herrlichkeit des Gekreuzigten. I am currently co-translating a selection of these Johannine essays with Wayne Coppins for his BMSEC series (scheduled for 2018). This 2016 volume contains almost all of the essays written by Jörg Frey on the other writings of the NT. Here is the description by the publisher that gives you a good idea of the breadth and depth of this project:

The second volume of collected essays by Jörg Frey contains 22 essays that illuminate the theological claims of New Testament texts from a philological and historical perspective. Issues discussed span the messianism of Jesus and the implicit Christology of his proclamation, the relevance of apocalypticism for Jesus, the different New Testament patterns of interpreting his death, and Paul’s background and development as well as questions on his theologies of justification and the cross. Further studies discuss New Testament concepts of salvation, the new covenant in Hebrews, ecclesiological and eschatological issues and the problem of the construction of a Theology of the New Testament. The author demonstrates that the New Testament is to be read both historically and theologically, and that its interpretation is also fruitful for issues of contemporary faith.

Also, note that the book opens with a new essay in which Jörg Frey describes his journey as a New Testament scholar and which offers invaluable insights into the current state of research.

Have you already circulated an updated wish list for Christmas in light of what you have read so far? Or have you decided to make yourself a present and have already begun shopping on the Mohr Siebeck-webpage? Excellent. However, I would at the same time also like to urge you to save a few bucks for the beginning of 2017! There are three books in particular I would like to include in this list – for they are all already with the publisher and near expectancy of their publication is truly justified.

Heilig, Christoph. Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context. Biblical Tools and Studies 27. Leuven: Peeters, 2017.

I assume you were not only disappointed not to meet me at this year’s SBL meeting but also because you couldn’t find this book on Peeters’ table. As I am told, your waiting should be over very soon. If you are interested in Pauline theology, Second Corinthians, the language of the New Testament, methodology, word studies, Graeco-Roman background of the NT, or the whole “Paul and Empire”-debate – or if you only want to finally get an answer to your nagging question of whether Paul portrays himself in 2 Cor 2:14 as a victorious general or rather a prisoner of war who is led to execution – this book might be of interest for you. Here’s the blurb from the Peeters webpage:

Paul’s metaphorical language in Second Corinthians 2:14 has troubled exegetes for a long time. Does the verb ‘thriambeuein’ indicate that Paul imagines himself as being led to execution in the Roman triumphal procession? Or is, by contrast, the victory in view that the apostles receive themselves? Maybe the Roman ritual does not constitute the background of this metaphor at all? Clarity with regard to these questions is a pressing issue in Pauline studies, given the fact that this metaphor introduces a central passage in the Pauline corpus that is of crucial importance for reconstructing the apostle’s self-understanding. Heilig demonstrates that, if all the relevant data are taken into account, a coherent interpretation of Paul’s statement is possible indeed. Moreover, Heilig brings the resulting meaning of Paul’s statement into dialogue with the political discourse of the time, thus presenting a detailed argument for the complex critical interaction of Paul with the ideology of the Roman Empire.

Kiffiak, Jordash. Responses in the Miracle Stories of the Gospels: Between Artistry and Inherited Tradition. WUNT II 429. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017.

My own book will look rather thin next to the dissertation (Hebrew University) by our peer mentoring group member Jordash Kiffiak. The page count on the Mohr Siebeck webpage has not yet been updated to reflect the pagination of the final version . It’s imposing, trust me. Now, if you are like me and you wonder how it is possible to say so much about such a specific issue, be assured: This is not simply an exhaustive discussion of an important element of the gospels, rather, this publication leaves no stone unturned in the study of the Gospels and the historical Jesus. This book will certainly be hotly debated in the coming year. You can get a sense of this by noticing the implications that are touched upon in the description:

Jordash Kiffiak offers the first concentrated study of a motif ubiquitous in the miracle stories of the gospels, namely the descriptions of characters’ speech, feelings, physical actions and the like in response to miracles. Conventional wisdom sees the response motif as a means of casting the miracle worker in a positive light. However, the author’s narrative-critical analysis argues that within each gospel the motif is employed creatively in a variety of ways. Responses serve to characterize various individuals and groups, both positively and negatively, sometimes in a more complex manner. They also contribute to the development of the plot, both in the individual episode and in the larger narrative. At the same time, observing that a network of features in the responses is shared among the gospels, Kiffiak argues that there is a common oral tradition behind the miracle stories, originating among the early followers of Jesus in the Galilee and/or Judea.

Frey, Jörg, Benjamin Schliesser, and Nadine Ueberschaer. Das Verständnis des Glaubens im frühen Christentum und in seiner jüdischen und hellenistisch-römischen Umwelt. WUNT. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017.

This is a massive project on the issue of “faith” from a variety of perspectives. For the rather impressive lineup, see the description on the Mohr Siebeck website.

Christoph Heilig is working on an SNF-Project on “Narrative-Substructures in the Letters of Paul” with Prof. Jörg Frey. He is the author of Hidden Criticism? Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul, WUNT II 392 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015) and Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context, BTS 27 (Leuven: Peeters, [apparently] 2017).

Abgelegt unter: From us or people associated with us

30. November 2016 |

Christoph Heilig |

1 Kommentar

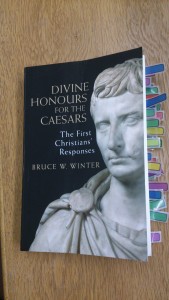

Recent years have seen a steadily growing interest in the question of how the parameters of society in the Roman Empire influenced the communities behind the New Testament texts and their respective authors. While some have argued that the NT texts indeed display critical interaction with this Roman sphere, others are more critical of assuming such conflicts and the idea that they are a kind of hermeneutical key for understanding the early Christians. This debate is probably best exemplified by the debate between N. T. Wright and John M. G. Barclay (which Theresa and I have analysed in an essay that has been discussed on this blog here).

This debate is probably best exemplified by the debate between N. T. Wright and John M. G. Barclay (which Theresa and I have analysed in an essay that has been discussed on this blog here).

If you are interested in my own take on the issue, you can read a short version of my argument on how this question should be evaluated for free here. I also have a book that develops these points into more detail. Furthermore, at the time of writing this post, there is a monograph in print with Peeters (see here), which exemplifies some of these considerations – including modifications of Wright’s hypothesis – with regard to Paul’s talk about the Roman triumphal procession in 2 Cor 2:14.

A book that has received quite a bit attention in recent times (it’s part of Mike Bird’s top ten list on “the NT and the Imperial Cult” and also included in Andreas Köstenberger’s list of the top ten books of 2015 ; cf. also Nijay Gupta’s remarks here) is Bruce W. Winter’s Divine Honours for the Caesars: The First Christians’ Responses.

I have written a review for the Journal of Theological Studies, which can be found here. If you don’t have access, you can read the pre-pub version on my academia.edu-webpage for free. However, I would also like to point you to an essay that has just been published on Reviews of Biblical and Early Christian Studies. It’s not simply a more extensive book review. Rather, I tried to enter a deeper conversation with Winter’s work by approaching it from my own specific point of view on this issue and by seeking (as I put it in the essay) “to set Winter’s contribution in the broader context of the study of the early Christians’ engagement with Roman ideology while focusing in particular on where his methodology might lead to promising results and where it falls short of the path chosen by other scholars.”

Christoph Heilig is working on an SNF-Project on “Narrative-Substructures in the Letters of Paul” with Prof. Jörg Frey. He is the author of Hidden Criticism? Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul, WUNT II 392 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015) and Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context, BTS 27 (Leuven: Peeters, [hopefully] 2016).

Abgelegt unter: From us or people associated with us

7. October 2016 |

Christoph Heilig |

2 Kommentare

I am very pleased to learn that the first part of the English translation of Michael Wolter’s commentary on the Gospel of Luke (originally published in the Handbuch zum Neuen Testament series) has just been released. This volume contains Wolter’s introduction to Luke and the commentary on the first 9 chapters of the gospel.

I had been working on this project over the last one and a half years or so, helping the main translator Wayne Coppins in his momentous task of bringing this extremely detailed work into English.

Wayne Coppins and Simon Gathercole – the editors of the BMSEC series – have already noted some good observations on Wolter’s commentary in their introduction. I want to use this opportunity to likewise point out two notable feature of Wolter’s commentary I particularly enjoyed.

My first comment relates to one of the most central motivations behind this blog – “bridging the German-English divide.” Wolter writes from a specifically German perspective, which differs from other academic traditions in many regards, including some basic hermeneutical decisions. Still, I think his commentary is exemplary in the way he integrates the work of other scholars from different spheres, particularly the work by more “conservative” English-speaking scholars (such as D. L. Bock, C. A. Evans, J.B. Green, I. H. Marshall, etc.). He neither ignores them nor does he ridicule them or enter into pointless discussions with them (which would be pointless because the real disagreement can’t be resolved on the level of exegesis). Rather, he a) notes their positions where he disagrees on exegetical matters because he simply follows a different scholarly path (thus making alternative positions visible as such – which is a heavily underestimated aspect, from my perspective) and b), where real interaction on the same level (i.e. on the basis of shared presuppositions) is possible, he enters into respectful dialogue with their arguments, sometimes benefiting from their work sometimes offering valuable criticism. In a certain way, this approach reminds me of Oda Wischmeyer’s take on N.T. Wright’s hermeneutics in GFP, which allowed her both to recognize hermeneutical differences without talking about them in an arrogant manner and to perceive of the strengths and the potential benefits of his paradigm. (Check out Wayne Coppins’s remarks on Wischmeyer’s essay, which express a similar judgement.)

The second comment I want to make is related to this aspect of interaction with other voices but focuses more on the specific contribution of a commentary writer and the proportion of unhelpful material he or she incorporates. Let me explain this a bit: Usually one does not read commentaries on biblical books cover to cover. But if you translate one you inevitably have to. Furthermore, I found translating a commentary more difficult than doing the same with other argumentative texts: in commentaries, the thoughts of the exegete are expressed in a very dense manner and he or she does not simply tell us what supports one major point but rather a multitude of things relating to a variety of textual phenomena. In translating a commentary you have to decide what precisely is being said in each and every proposition for otherwise you might accidently create new exegetical remarks. In that regard my impression was that Wolter made a big effort to make it clear what he actually wants to communicate. This is only possible, to be sure, if the author is offering his or her unique opinion, offering a truly “eigenständig” conception. Sometimes in commentaries you notice a certain vagueness that is probably due to the commentator trying to summarize the results of other persons while not having an own opinion that would help him or her navigate through these proposals. Not so in Wolter’s commentary on Luke: it is clear that he doesn’t write just for the sake of having said something on a particular textual feature. Rather, where he comments on the text this is because his prior research has made him come to the conclusion that he actually has something meaningful to say about that issue.

Thus, in conclusion – unsurprisingly perhaps but all the same wholeheartedly – I warmly recommend this publication to you. Also, stay tuned for the second volume, the publication of which is scheduled for 2017.

Christoph Heilig is working on an SNF-Project on “Narrative-Substructures in the Letters of Paul” with Prof. Jörg Frey. He is the author of Hidden Criticism? Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul, WUNT II 392 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015) and Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context, BTS 27 (Leuven: Peeters, 2016).

Abgelegt unter: From us or people associated with us⋅ New Publications

3. October 2016 |

Ruth Friederike Kunath |

Keine Kommentare

Recently, de Gruyter published my book Die Präexistenz Jesu im Johannesevangelium. Struktur und Theologie eines johanneischen Motivs, which is a revised version of my PhD dissertation (Humboldt-University Berlin). In this blogpost, I shall present my findings, highlighting some central aspects, especially the role of temporality for John’s notion of preexistence.

The Gospel of John has been said to dare the impossible, the “quadrature of the circle”. The German theologian Karl-Josef Kuschel used this metaphor for characterising the Johannine attempt of narrating the un-tellable.[1] John tells us a story about the preexistent Christ – that is, John transforms an idea connected to eternity and nontemporality into a narrative line connected to temporality.[2] Kuschel calls this the “verwegene Synthese”[3] (daring synthesis), where John synthesizes a story of Jesus and the concept of preexistence, both of which occur, outside of John, only in separate texts. The Synoptic Gospels have at least no explicit reference to preexistence,[4] but start with Jesus’s baptism (Mark) or his virginal conception (Luke and Matthew). Preexistence outside of John is attested only in short, hymn-like passages or formulae within the epistolary literature (Phil 2, Col 1 and others) and Revelation.

Kuschel and other scholars think of the notion of preexistence as something which at its core is not connected to temporality.[5] Talk of preexistence might use the language of temporality, but its actual meaning concerns Jesus’s significance and his belonging to the realm of God. For most scholars therefore, preexistence in the Gospel of John is expressed in a variety of motifs, including the language of sending, oneness, descending and ascending, and various facets of the text that have to do with Jesus’s exclusive connection with his heavenly father and the heavenly realm.[6] In short, it is supposed that preexistence deals with everything expressing Jesus’s superhuman or godly side.

Following Kuschel’s observation that John narrates preexistence and that this concept is highly innovative, the aim of this blogpost is twofold. First, I shall highlight the significance of temporality for the preexistence of Jesus in the Gospel of John, laying open the motif’s clearly structured, temporal function within the overall narrative of the Gospel. Second, I shall make a proposal regarding how this motif could be related to experiences of time and temporality in the lives of the original (ideal) readers, as well as of readers in our time. I shall conclude that because of – not despite – of its temporality, the preexistence of Jesus in the Gospel of John gains in meaning and significance.

Is Jesus’s preexistence in the Gospel of John conceptualised temporally?

My starting point for analysing Jesus’s preexistence in the Gospel were seven statements that express clearly the temporal existence of Jesus or the Logos prior to someone or something else. Preexistence in my approach denotes a linguistic and therefore visible phenomenon in a given text – specific sorts of expressions. While most scholars understand preexistence to denote an idea or mental construct, my approach identifies seven phrases in the Gospel of John which are employed in a similar syntactic-semantic way.

Using a lexeme denoting temporal priority (“before”), each of these sentences makes a claim that, explicitly or implicitly, pertains to Jesus’s being. These statements are as follows.

- John 1:1a, 2: the narrator states that in the beginning was the Logos.

- John 1:15, 30: John the Baptist testifies that Jesus, though coming after him, already existed before him.

- John 6:62: Jesus, in dialogue with skeptical disciples, announces the (future) ascent of the Son of Man to where he was before.

- John 8:58: Jesus provokes his dialogue partners, “the Jews”, by telling them that even before Abraham came into being Jesus existed.

- John 17:5: in the farewell prayer, Jesus asks his heavenly father to glorify him in the glory he already had before the world existed.

- And, finally, John 17:24: Jesus prays for all the believers to be with him and see his glory, which he has from God, because God loved him before the foundation of the world.

When one looks at these seven statements together, the changing temporal points of reference may appear puzzling. There is no unified notion of preexistence in terms of a fixed temporal reference point. Rather the statements run through the Gospel in a temporally dynamic way. In the prologue we are told in an abstract way about the “pure” existence of the Logos in the beginning, with God, and of him himself being God. Then the incarnated Logos is identified by the Baptist as the one who comes after him but existed before him. It is here in John 1:15 where the motif of pre-existence actually starts. The preexistence is a paradox. Yet it spans only a short time, since the Baptist is a contemporary of the earthly Jesus. Following this instance of the motif, the time gap that the earthly Jesus bridges becomes greater, Consecutively it is revealed that he existed prior to the time of his descent, of Abraham’s birth, and, finally, of the foundation of the world. As the plot of the Gospel unfolds, the temporal depth of the protagonist Jesus becomes deeper and deeper. The climax in the use of the motif, which reveals Jesus’s precreational existence, is expressed just prior to the passion and Easter narratives. These moments are the center of the “hour”, the climax of the Johannine story as a whole. This means that the preexistence motif participates in and contributes to the dramatic arc of the Gospel’s storyline.

Let us take a closer look at the connection between the preexistence statements and the larger narrative framework. The statements are strategically located within the Gospel and each of them interacts profoundly with the plot. In my book, I go very much into detail about how each statement functions within its immediate context. In John 1:15 and 30, Jesus’s paradoxical existence prior to the Baptist, though Jesus nevertheless comes after him, relates to the incarnation of the Logos, as well as to the first appearance of Jesus in the narrative. The Baptist here revisits the topic of Jesus’s mysterious, hidden presence and his open activity – a topic that is unfolded broadly within the passage of John 1:19-35.

John 6:62 and 8:58 are carefully placed within the context of chapters five through ten, a section that is characterised by the numerous conflicts Jesus has with different groups. John 6:62 is embedded in a conflict between Jesus and a group of disciples that, at the end of the interaction, finally leaves him. The preexistence statement is part of Jesus’s answer to the disciples’ refusal to accept his living bread discourse. The discourse contained disturbing hints of Jesus’s violent death and voiced the expectation that his disciples would eat and drink his flesh and blood. Rather than ameliorate the situation, Jesus, in his statement in verse 62, increases the challenge posed by his words, now talking about a future ascent (and return) to his heavenly origin. How are the disciples supposed to connect his violent death to his claim to return to God in heaven, “to where he has been before”? Preexistence functions here as a clear hint of the real meaning of Jesus’s death – but only for the informed and believing reader. For the disciples in the story the statement magnifies the stumbling block they see in Jesus’s words.

Similarly, John 8:58 plays a central role in one of the most heated debates between Jesus and “the Jews”. Here, though, the preexistence statement is the catalyst for a decidedly more negative reaction, namely the interlocutors’ attempt to stone Jesus. This is directly connected to the form of the preexistence statement, in which Jesus presents himself as prior to Abraham, to whom the Jews appeal in order to reject Jesus’s challenging request to believe in his words.

Finally, John 17:5 and 24 are part of Jesus’s farewell prayer and therefore – complementarily to John 1:15, 30, at the opening of the Gospel – placed within the departure of Jesus. Both verses address directly the completing of Jesus’s departure as his glorification, which occurs in his “hour”. The references to his precreational being in this context are related to his twofold relationship to the world. On the one hand he is leaving the world and has never been part of it. On the other hand, his salvific action that is taking place in the “hour” aims at the world in that, through it, he sends the believers into the world. In his “hour”, Jesus acts in a way that corresponds to the creation of the world. Therefore he asks his father to glorify him with his precreational glory.

In the Gospel of John, therefore, there is no categorical difference between historical preexistence (existence before the Baptist and before Abraham) and precosmic or “eternal” existence. Rather, the notion of preexistence is developed both temporally and dynamically. This development is a movement of Christ through time to beyond the beginning of the world.

What significance may the preexistence of Jesus and its temporality have to the reader? – A suggestion

Having shown the crucial role that temporality plays for the development of the concept of Jesus’s preexistence in the Gospel of John, I shall now turn to the reader. What does the preexistence of Jesus mean to the implied audience? Is it a doctrine that the audience is meant to believe in? Is it rather, as Larry Hurtado puts it, an expression of their devotional practice?[7] The answer that I am suggesting here is a cautious one. Although John contains the most elaborate and explicit preexistence Christology in the New Testament, nevertheless from a careful analysis of the seven preexistence statements within their narrative contexts, the categories of both doctrine and devotion do not seem to adequately represent the Johannine preexistence motif.

Is it not striking that not one explicit preexistence statement is uttered or even answered positively by a believing figure, comparable to Martha’s confession in chapter 11 or Thomas’s confession of Jesus being his Lord and God in chapter 20? John 1:30 is said by the Baptist who plays an exceptional role in the story as witness and mediator of God’s revelation (cf. John 1:32). His preexistence statement is not answered by another figure; it is not even clear in the story who is listening to him speak. The two statements in John 6 and 8 are strongly connected to doubt and unbelief. In the first case, a group of skeptical disciples leaves Jesus―obviously his preexistence statement could not persuade them to stay and possibly it even strengthened their skepticism. In chapter 8, the provocative function of Jesus’s preexistence statement is clear―his Jewish dialogue partners intend to stone him immediately thereafter. In chapter 17, Jesus is talking exclusively to his heavenly father without any other characters bearing witness or reacting to the christological statements.

In my opinion one can conclude that, for John, Jesus’s preexistence is not an easily nor broadly accepted Christological statement. It is part of a struggle about Jesus’s identity and true being. Thus, John does not put it into the mouth of a believing character. Preexistence here is highly provocative. It stands on the edge between the acceptable and the unacceptable, neither easily incorporated into the devotional practice of the community nor even reflecting such a practice.

But is it possible to say something more about what Jesus’s preexistence might have meant for the intended readers of John’s Gospel? I would like to venture a possible answer. The Baptist’s testimony of Jesus having already existed before him, though he became visible only later (John 1:30), is related closely to the scene in John 1:47-51, where Nathanael becomes Jesus’s disciple. Nathanael is called by Philip and when Nathanael comes to meet Jesus, Jesus greets him by calling him “a true Israelite”, one in whom there is “no deceit.” (John 1:47) Nathanael wonders how it is that Jesus already knows him. Jesus’s answer is enigmatic: “Before Philip called you, I saw you under the fig tree” (John 1:48).

We can leave aside here the precise meaning of “seeing someone under the fig tree” and focus rather on the first part of the sentence, which points to Jesus’s pre-knowledge. Jesus’s pre-knowledge in this scene and Jesus’s preexistence attested by the Baptist share a parallel structure: Jesus is unknown to the Baptist and to Israel before his ministry but is revealed by the testimony of the Baptist. His earthly ministry is not the beginning of his existence, but he was there even before the Baptist. Likewise, Nathanael, as the “true Israelite”, experiences this insight. He is led to Jesus by a mediator, Philip, and recognizes that Jesus is already connected to him and that Jesus is to some extent “preexistent” in the life of Nathanael. The preexistence of Jesus can be seen as closely connected to the life of the believer.

Preexistence is therefore not an “objective” Christological feature that can be determined without reference to the experience of the believer. It gains meaning when seen in the context of the experience of time in one’s life. Preexistence is related to the insight that the beginning of belief in Jesus is preceded by Jesus’s mysterious presence in one’s life.

Conclusion

In my book, I argued that a clear, crafted motif of Jesus’s temporal preexistence, consisting of seven statements, permeates the Gospel from chapter one to the end of chapter 17. At its core the motif unfolds a notion of Jesus’s existence prior to several other entities, with an ever increasing temporal extent, reaching beyond the Baptist, beyond Abraham, beyond even the foundation of the world. The exposition of the preexistence concept runs through the narrative as a temporal line parallel to the narrative’s unfolding and is deeply connected to the narrative’s dramatic arc. The culminating moment of the preexistence motif (John 17:5.24) corresponds to the climax of the Gospel as a whole, namely Jesus’s “hour”. At the same time – and paradoxically – knowledge of the extent of Jesus’s preexistence, as it is successively revealed, also runs in a line parallel to the unfolding of the narrative, albeit in the opposite chronological direction. Thus it is due to the temporality of the motif that Jesus’s preexistence gains meaning and significance for John’s readers.

Dr. Friederike Kunath is working on her Habilitation about Paul’s ethics in the context of an embodiment-approach with Prof. Jörg Frey. She is the author of Die Präexistenz Jesu im Johannesevangelium. Struktur und Theologie eines johanneischen Motivs, BZNW 212 (Berlin: de Gruyter: 2016).

[1] Karl-Josef Kuschel, Geboren vor aller Zeit? Der Streit um Christi Ursprung (Munich: Piper, 1990), 469: “Wie soll man von etwas erzählen, das sich im Unanschaulichen ‘vollzieht’”? “Eine einzige christliche Gemeinde wagt gegen Ende des 1. Jahrhunderts den Versuch einer Quadratur des Kreises: die Gemeinde des Johannes.”

[2] Cf. Kuschel, Geboren, 469.

[3] Kuschel, Geboren, 468.

[4] Simon Gathercole, The Preexistent Son. Recovering the Christologies of Matthew, Mark, and Luke (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), argues that the synoptic gospels implicitly contain a preexistence Christology.

[5] Cf. Kuschel, Geboren, 644; Rudolf Bultmann, Theologie des Neuen Testaments (6th ed., Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1968), 414f. The opposite view is found for example in William Loader, The Christology of the Fourth Gospel. Structure and Issues (2nd rev. ed.; Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1992), 153.

[6] Cf. for example, Loader, Christology, 43, 48, 51f; Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 365-369.

[7] Cf. Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ, 370.

Abgelegt unter: From us or people associated with us⋅ New Publications

22. September 2016 |

Christoph Heilig |

1 Kommentar

For Part 1 of this series, see here. For Part 2, see here.

Jörg Frey: Demythologizing Apocalyptic?

Imagining a debate between two scholars of such status as N. T. Wright and Jörg Frey, you might think of a confrontation of truly “apocalyptic” dimensions. And at least with regard to the page count, this expectation is fulfilled by what you will find in God and the Faithfulness of Paul. On 42 pages, Frey offers an introduction to the apocalyptic interpretation of Paul, its prospects and limits, and argues that Wright is to a certain extent “neutralizing” what he regards to be essential characteristics of apocalyptic texts. Wright returns the compliment of exhaustive interaction by responding in 1/5 of his essay “The Challenge of Dialogue.”

Frey opens directly by stating that it is “easy to observe that apocalyptic elements in Paul’s letters and thought have been assigned only a marginal place in Wright’s map of Paul’s mind” (GFP 489). In particular, he points to the “polemical and ironizing mention of those interpreters advocating an apocalyptic reading of Paul” throughout the book (ibid.). Frey suspects that Wright’s sensitivity for this issue might be due to the fact that this parameter could be the Achilles heel of Wright’s great narrative as interpretative framework (GFP 490).

In the first major section of his essay, Frey identifies four strategies in PFG to “tame or neutralize Pauline apocalyptic language” (GFP 490):

- The symbolic reading: Wright assumes (following Caird) that “biblical authors already knew that the world as a whole would not actually come to an end. They used and reused language, aware that it did not literally mean what they said” (GFP 493). Here Frey argues that “things are more complicated” (494) and concludes with regard to Paul: “Paul actually hoped for such change [as associated with the Parousia of Christ], and if we let Paul be Paul and do not create him according to our likeness, we should allow him to do so” (495).

- The socio-political reference: Here Frey doubts “whether the political dimension can be the general clue for understanding apocalyptic language,” arguing that even where a political dimension is present this does not “rule out the possibility that the author seriously imagined a transcendent reality intervening in the present world” (GFP 496).

- The presupposed “covenantal” worldview: Here Frey criticizes Wright for prioritizing the parameter of “worldview” in interpreting apocalyptic language: “The precise images, motifs, and terms do not matter because their real meaning is already determined by the presupposed worldview, the overall story or – as we might call it – the Wrightian ‘myth of redemption’” (GFP 497).

- Inaugurated eschatology: In this section, Frey claims that Wright downplays sections in Paul’s letters (e.g., 1 Thess 4:16-17) that are explicit with regard to future eschatology: “This is also an apologetic strategy. If something is unimportant, it disappears from focus” (GFP 499). By this classification, Frey means that “if we claim Paul as the predominant testimony for contemporary Christianity, we are always tempted to eliminate views that appear strange, mythological, or unbelievable and stress the ‘already’ (and search for any evidence that Paul himself already did so when interpreting his traditions)” (501-502).

Having put forward this criticism, Frey offers a lengthy excursus on the apocalyptic interpretation of Paul, focusing on Käsemann, Martyn and de Boer (GFP 502-512). This is followed by a synthesis of “recent perspectives” on apocalyptic literature (GFP 512-520), thus aiming at offering corrections to the notion of “apocalyptic” as found in both Wright’s PFG and the work of his “adversaries” (GFP 513). He concludes (GFP 520): “We can see that the concepts of apocalyptic applied by Käsemann, Martyn, and the Boer are inappropriate in view of the variety of the Jewish apocalyptic texts. But on the other hand, Wright seems to underestimate the variety of apocalyptic concepts as well. Not all of these texts share the Deuteronomistic pattern developed from the end of Deuteronomy and from Dan 9” (GFP 520).