Introduction

Reflecting upon the different events we had staged during 2016, the fact attracted my attention that we had had three workshops on various aspects of ancient languages and that they – even though they dealt with quite different issues and even though I would not want to claim that it is possible to identify a “core” of convictions the presenters shared – mutually re-emphasized each other. We began with a workshop by Heinrich von Siebenthal on his approach to analyzing Greek texts from a linguistic point of view. I contributed a workshop on lexical semantics and the importance of the Online TLG corpus in determining both semantic range and discourse meaning of Greek words. Towards the end of the year, Jordash Kiffiak introduced us to a modern approach to learning ancient languages that is increasingly gaining a following. The last mentioned topic deserves a blog post on its own and I have already written about my thoughts on “word studies” elsewhere on this blog. Hence, I will focus here on the event with Heinrich von Siebenthal. Nevertheless, I think it might be interesting for our readers to point out some connecting elements between his approach and the other two events on ancient languages that took place last year.

Heinrich von Siebenthal on “Lexical-Grammatical and Semantic-Communicative Analysis”

If you know anything about the German tradition of Greek grammars, it is probably because you have worked with “Blass-Debrunner-Funk” in the past. This is the English revision of a project that had originally been published in 1896 (!).In many ways, of course, this work remains an excellent Greek grammar. Nevertheless, in other respects both BDF and its German counterpart (“Blass-Debrunner-Rehkoph”) can no longer be trusted. But while there are by now multiple alternatives in the English-speaking sphere, BDR still remains quite influential among German-speaking exegetes. This is quite unfortunate, since the whole section on the verbal system is untenably outdated. Even if one broadens the view beyond grammars that deal specifically with the New Testament, the situation is astonishingly sparse: The standard school grammar by Bornemann-Risch dates to 1978 (and is also quite problematic with regard to the verbal system) and the most detailed scholarly grammar by Kühner-Blass-Gerth is (even in the latest revision by Gerth, which has, by the way, just been reprinted by the WBG in 2015!) more than 100 years old …

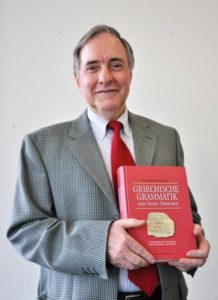

Against this background, the significance of Heinrich von Siebenthal’s grammar on the Greek of the New Testament (Griechische Grammatik zum Neuen Testament [Gießen: Brunnen/Immanuel, 2011) – a heavily reworked version of his earlier publication together with Hoffmann (1985 and revised in 1990) – should be apparent. His grammar is also available in Logos and I believe there are plans for a translation.

Just recently, von Siebenthal has made a similarly pioneering contribution to Hebrew grammar through his Grammatik des Biblischen Hebräisch (building on the work of Jan P. Lettinga), finally offering an alternative to the grammar by Wilhelm Gesenius – which to this day is reprinted in the form of the 28th edition (revised by Emil Kautzsch) from 1909 (with the English translation by Ernest Cowley having been published in 1910)!

It was a great honor for us that we were able to begin our activities with a workshop by von Siebenthal on the method that he has taught for decades for analyzing the text of the New Testament.

This approach can even be recognized by taking a look at the grammar itself: What is notable is not simply the fact that it incorporates more recent research on hotly debated issues such as the verbal system (on this topic, see this post by Wayne Coppins), but also the fact that it ends with a long section on “text grammar” (§297–§354). Thus, von Siebenthal is obviously not only concerned with offering tools for deciphering syntactical structures on the level of clauses and sentences but also with texts – how they are structured and how they are to be understood!

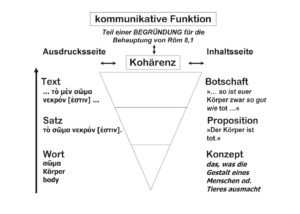

While the grammar offers a summary of the categories that are relevant in that regard, von Siebenthal has described the analytical steps that are necessary to that end elsewhere in more detail, namely in his essay “Linguistische Methodenschritte: Textanalyse und Übersetzung” (Pages 51–100 in Das Studium des Neuen Testaments: Einführung in die Methoden der Exegese. Revised Edition. Edited by Heinz-Werner Neudorfer and Eckhard J. Schnabel. Wuppertal: Brunnen, 2006). The foundations of this approach from the perspective of general linguistics are, unfortunately, only available in the chapter “Sprachwissenschaftliche Aspekte,” which had been published in an earlier version of that text book (Pages 69–154 in Das Studium des Neuen Testaments. Vol. 1: Eine Einführung in die Methoden der Exegese. Edited by Heinz-Werner Neudorfer and Eckhard J. Schnabel. Wuppertal: Brunnen, 2000). In most general terms, von Siebenthal’s approach centers around the conviction that for exegetes it is important to take into account both the “expression” side and the “content” side of textual structure.

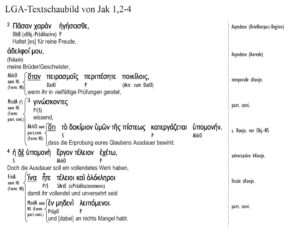

The first step – the lexical-grammatical analysis – aims at making the syntactical structure of a passage visible (the example is James 1:2–4).

As you can see, each clause and also each textual feature that has an equivalent function (“satzwertige Konstruktionen,” i.e. participles, etc.) gets assigned to a new line and is indented if it is grammatically subordinate.

In a next step – the semantic-communicative analysis – von Siebenthal wants us to focus on the corresponding propositions and how they form a semantic structure. The individual elements of the lexical-grammatical analysis form the point of departure for this step. Even action nouns and prepositional phrases that function attributively can function as the point of departure for a proposition. However, what we are now putting in relation to each other are not the Greek expressions themselves but rather elements of meaning (which we express by using the sign system of our modern languages due to the fact that we lack competencies to do so in the original language). So while the semantic-communicative analysis remains related to the level of expression, a different set of features is focused on here. As a result of this step, we might get a hierarchical structure of the semantic relations within a passage that looks like this:

There are several reasons for why I think that every exegete should work on his or her text at least once from this perspective:

-

Often, we read exegetical arguments that do not in fact incorporate all the elements of the text. There is a focus on a specific word or cross-connection but it is not demonstrated how the passage as a whole is structured in a way that the interpretation of this individual element fits in.

-

What is true on the level of lexical semantics is all the more true on the level of textual semantics: In order to support their theses, biblical scholars quite frequently oscillate between the level of expression and the level of content, without signaling this sufficiently. If one wants to make any argument about the meaning of a text, it is however necessary, a) to explain how the postulated semantic network arises on the foundation of the linguistic actualities and b) how this network itself is structured.

-

The method is very practical in that it combines semantics and pragmatics. In other words, the “thing” we want to determine in the semantic-communicative analysis is what the author wanted to communicate to his audience. Therefore, a lot is to be included in this diagram that needs to be supplied from our analysis of the historical background, literary context, etc. Although it should go without saying, it might perhaps be worth stressing that von Siebenthal’s approach does not offer a linguistic-bulletproof method for introducing these elements, which must, of course, be collected within the methodologically appropriate tools. However, where von Siebenthal’s framework is really helpful is in making visible the precise points at which we supply such information and how this information changes the overall content. Sometimes when I read long sections in a commentary on a specific biblical passage that is difficult to understand, I wonder whether the author would have been able to supply me with such a semantic-communicative analysis. For the paraphrase that results in this step is, after all, nothing but the densest formulation of a commentary in the best sense, i.e. an explication of what the text in question is meant to express. My guess would be that all too often commentators would not be able to bring their exegesis into such a form – which would raise the question of whether the much longer – but with regard to content rather poor – explanations are worth the paper they are published on.

-

This leads me to the final advantage of von Siebenthal’s approach as I see it. There is not only a heuristic gain inherent in it. It also helps us to better communicate about our exegesis by offering structures and categories. Often, when we discuss research papers, we simply point to a particular aspect we did not really like for some reason or for which we happened to know some facts by coincidence. However, it is at least not unusual that it is unclear how our contribution affects the actual argument of the presenter. Having a clear structure of the text – both of the level of expression and the level of content – before us, we can, by contrast, easily identify crucial issues and how they relate to the overall interpretation, e.g., by discussing how γινώσκοντες in James 1:3 should be understood and how this influences our reconstruction of the “Kommunikat” (that which is communicated).

If you are interested in performing such an analysis yourself, you can use this free software (link), which is really helpful for connecting propositions. If you are looking for an English-speaking introduction I suggest you familiarize yourself with the work of the “Summer Institute of Linguistics” and with, what they call, “Semantic Structure Analysis” (link), which had served as point of departure for von Siebenthal’s own methodological sketch.

There are, of course, some limitations to this approach but this does not, in my opinion, diminish the necessity to do something along these lines in the process of trying to understand what an ancient author attempted to communicate. What is noteworthy is the fact that von Siebenthal is quite traditional with regard to the nature of connectors. One might want to compare his holding on to different meanings of connectors such as δέ with the discourse grammar by Steven E. Runge. Still, I would like to advocate that this by no means implies that von Siebenthal’s assumes an outdated notion of ‘text,’ in which a text is nothing more than a collection of sentences and is to be analyzed by the same set of tools as the smaller units. Quite the contrary is the case! Von Siebenthal explicitly builds on the textual notion of Christina Gansel and Frank Jürgens (Textlinguistik und Textgrammatik, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), who advocate an “integrative text model,” which incorporates communicative (and, thus, social) functions. So, if there is a danger with regard to misusing von Siebenthal’s methodological approach, I would argue that it resides in an outdated of the concept of “text” on the side of potential users.

On Learning and Understanding Languages

This last consideration leads me to a workshop that we have had only very recently. Jordash Kiffiak is one of the very few people worldwide who teach Koine Greek, Biblical Hebrew, and Classical Syriac as spoken languages. He learnt to speak Hellenistic Greek from both Randall Buth (Biblical Language Center) and Christoph Rico (Polis – The Jerusalem Institute of Languages and Humanities) during his time living in Jerusalem and the communicative approach he uses makes use of modern pedagogical insights, such as James J. Ashers “Total Physical Response” method and Ray Blaine’s and Contee Seely’s emphasis on storytelling in achieving fluency. Kiffiak’s use of a communicative approach is especially indebted to his time teaching for the Biblical Language Center and to mentoring by Randall Buth in particular. He is the co-author of a new beginner’s textbook for Christian Aramaic (i.e. Syriac) that is to be published in 2017.

Kiffiak will himself introduce in due course on this blog the method he uses. What I would like to do here is to draw some connecting lines – as they appear to me – to what von Siebenthal has taught us.

In this particular workshop, Jordash Kiffiak first gave us a general introduction into the foundations of this method of learning ancient languages and then demonstrated his points by making us learn quite a bit of the basics in Syriac in only two hours – and in a very playful and low-stress way. At the end of the workshop he gave a brief demonstration, immersed now in Hellenistic Greek, of how intermediate students can be lead through a discussion of an unadapted ancient text, using comprehensive questions in the target language.

Now, at first sight this whole event might seem to stand in a rather stark contrast to von Siebenthal’s quite theoretical analyses. However, the more I think about it the more the two approaches seem to go hand in hand. After all, Kiffiak’s work aims at learners internalizing as much of the core vocabulary, forms and structures in a given language as possible. The approach, therefore, is not simply about learning a language without having to experience the headache of memorization using flashcards. In other words, it would certainly be wrong to think that such an approach is perhaps suitable for students who are not very serious about ancient languages but not so much for people enrolled in a biblical studies program. Quite the contrary is the case. While most students who learn languages such as Ancient Greek through traditional methods never achieve fluency and are often not even able to read a simple piece of text from the New Testament without the assistance of software, Kiffiak’s approach specifically aims at preparing people for being able to read and understand texts written in Koine Greek without such tools.

Also, it became clear to me as I continued to reflect upon my experience during this wrkshop that Kiffiak’s work is not just about different didactic strategies. It has also very significant implications for how we as exegetes approach the texts we are working on. And in that regard I suddenly realized that von Siebenthal’s and Jordash Kiffiak’s contribution to our attitude towards ancient languages such as Koine Greek is actually quite similar. For the majority of features unique to von Siebenthal’s grammar are, after all, associated with his linguistic indebtedness to text linguistics and are, thus, much more concerned with the actual regularities of texts than this is the case in every other Greek grammar I know. Just compare what Gansel and Jürgens (3rd ed.; 2009, p. 175) say about their compilation of “text-grammatical structures” of the German language. They are aiming at:

“… eine realistische Grammatik des Deutschen in geschrieben und gesprochenen realisierten Textsorten vorzulegen, eine Grammatik, die den realen Sprecher/Hörer und Schreiber/Leser in den Mittelpunkt stellt und die Regelhaftigkeiten des Sprachgebrauchs in Texten/Textsorten herausarbeitet. Strukturelle Gegebenheiten der natürlichen gesprochenen Sprache sind also ausdrücklich ein expliziter Bestandteil einer solchen Grammatik.”

(My translation:)

“… to produce a realistic grammar of German as it appears in text sorts of both written and spoken realization – a grammar, which places the real speaker/hearer and writer/reader into the focus and works out the regularities of linguistic usage in text/text sorts. Structural actualities of the natural spoken language are, thus, emphatically an explicit part of such a grammar.”

Analogously, von Siebenthal’s Greek text grammar includes features such as “Mitzuverstehendes” (e.g., semantic and logical presuppositions; §314). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that although von Siebenthal’s text book on Koine Greek (Grundkurs Neutestamentliches Griechisch [Giessen: Brunnen, 2008]) is methodologically quite different from Jordash Kiffiak’s approach at first sight – in that it encourages to explicitly memorize many rules of how to translate Greek clauses – even here it still shares some common ground. Von Siebenthal’s book builds on a method developed by Otto Wittstock that makes use of insights from simultaneous translating of modern languages. Students are meant to learn reading Greek texts in a way that is similar to how professional interpreters work. While translation is not a key component of Kiffiak’s approach, the simultaneous translation of modern languages has in common with Kiffiak’s communicative approach to learning ancient language an emphasis on processing communication at the rate of speech.

Why is all this relevant for our actual exegetical work? Well, I would like to argue that how we study a specific text is necessarily influenced by what we explicitly and implicitly hold to be true about the language it is written in. What I have become increasingly aware of is the fact that these presuppositions are also shaped by how we have learnt that language. As Michael Jost, researcher at the University of Bern and member of our Peer Mentoring Group, put it after the workshop: “We tend to treat these dead languages as if they had always been dead!”

There are two areas that come to my mind specifically in which both the emphases of von Siebenthal as well as the pedagogical approach of Kiffiak might help avoiding exegetical fallacies by giving us a more realistic notion of what these ancient languages actually are.

- First, while exegetes usually do not justify their exegetical moves through analyses as taught by von Siebenthal, on the one hand, they sometimes point to very specific textual phenomena and refer to what they think are strict grammatical rules, on the other hand, to make a point about a tiny detail of the text – which then in turn influences how the whole passage is interpreted. Knowing a bit of modern Greek, I cannot but wonder whether this way of doing things does not often mistreat the texts as raw material for speculations mostly fed by our lack of familiarity with the language itself. Interestingly, aiming for over-precision (and justifying it by referring to grammatical categories no native speaker would have been able to understand, such as a separate genitive for almost every noun) was the number-one-concern of von Siebenthal, when we asked him at the workshop what kind of problems he most often sees in exegetical literature from his linguistic perspective.

- Second, in the area of lexical semantics von Siebenthal’s and Kiffiak’s different approaches have a similar significance in relation to a consideration that is quite important in my mind. I do not want to go into the details of my own workshop on lexical semantics and the TLG corpus here because it basically was a summary of my research that has recently been published by Peeters and for which I have written a separate blog post.

However, what I would like to point out here is that I have personally profited a lot from von Siebenthal’s semantic-communicative emphasis with regard to determining the discourse meaning of a specific word in a given NT passage. Similarly, I think that it can be shown on the basis of considerations from the field of the philosophy of science (see for this the essay I co-authored with Theresa Heilig) that in order to determine how a word is used in a NT passage, it is of immense significance to be familiar with what the paradigmatic options would be – i.e. familiarity with other words that could have been used in that place of the syntactical structure. In other words (offering a short summary of what I wrote in the other post on word studies), what happens quite often is that students (and sometimes also more senior scholars) of the NT make decisions concerning the semantics of an expression in the passage under consideration on the basis of that word being most often used with a certain meaning. What they too often ignore entirely, however, is whether it might be the case that this ratio of meanings for that lexeme is simply due to the fact that this semantic content is expressed quite rarely in general. If that were the case, the fact that a meaning occurs towards the end of our dictionary entry is almost completely irrelevant for deciding whether this is the meaning we should assume in a specific passage. It could still be the most probable meaning for that text! What we need to focus on instead is the question of whether there would have been more likely lexical solutions for this semantic-communicative problem (and what kind of “content” the context makes us expect regardless of the actual lexical choice). That is to say, we have to know what lexical alternatives a native speaker would have had to express the same concept. This is, of course, a question no dictionary can answer for us and a competency students usually do not develop at all – for it requires a familiarity with the language that goes beyond translation equivalents, i.e., a Sprachgefühl as students could develop if they learnt their ancient languages along the lines of the method Jordash Kiffiak uses in his teaching.

However, what I would like to point out here is that I have personally profited a lot from von Siebenthal’s semantic-communicative emphasis with regard to determining the discourse meaning of a specific word in a given NT passage. Similarly, I think that it can be shown on the basis of considerations from the field of the philosophy of science (see for this the essay I co-authored with Theresa Heilig) that in order to determine how a word is used in a NT passage, it is of immense significance to be familiar with what the paradigmatic options would be – i.e. familiarity with other words that could have been used in that place of the syntactical structure. In other words (offering a short summary of what I wrote in the other post on word studies), what happens quite often is that students (and sometimes also more senior scholars) of the NT make decisions concerning the semantics of an expression in the passage under consideration on the basis of that word being most often used with a certain meaning. What they too often ignore entirely, however, is whether it might be the case that this ratio of meanings for that lexeme is simply due to the fact that this semantic content is expressed quite rarely in general. If that were the case, the fact that a meaning occurs towards the end of our dictionary entry is almost completely irrelevant for deciding whether this is the meaning we should assume in a specific passage. It could still be the most probable meaning for that text! What we need to focus on instead is the question of whether there would have been more likely lexical solutions for this semantic-communicative problem (and what kind of “content” the context makes us expect regardless of the actual lexical choice). That is to say, we have to know what lexical alternatives a native speaker would have had to express the same concept. This is, of course, a question no dictionary can answer for us and a competency students usually do not develop at all – for it requires a familiarity with the language that goes beyond translation equivalents, i.e., a Sprachgefühl as students could develop if they learnt their ancient languages along the lines of the method Jordash Kiffiak uses in his teaching.

Christoph Heilig is working on an SNF-Project on “Narrative-Substructures in the Letters of Paul” with Prof. Jörg Frey. He is the author of Hidden Criticism? Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul, (Mohr Siebeck, 2015) and Paul’s Triumph: Reassessing 2 Corinthians 2:14 in Its Literary and Historical Context, (Peeters, 2017). Additionally, he has co-translated (with Wayne Coppins, the main translator and editor of the project) Michael Wolters The Gospel According to Luke and co-edited (with J. Thomas Hewitt and Michael F. Bird) God and the Faithfulness of Paul: A Critical Examination of the Pauline Theology of N. T. Wright (Mohr Siebeck, 2016).

2 Kommentare vorhanden

1 Ancient Languages | These things are written // Feb 25, 2017 at 23:00

[…] those interested in ancient languages, there is a substantial and interesting post on the Zürich New Testament Blog, which pays particular attention to the important work of Heinrich von […]

2 On Mastering Koine Greek // Mar 9, 2018 at 15:07

[…] Due to my dissatisfaction with my Greek language skills, I continued to keep my eyes open for other approaches that might get me to a point that I deemed desirable. I had been using the “reconstructed” pronunciation by Randall Buth for some years already, when I met Jordash Kiffiak in Zurich. Jordash had been involved in the development of the approach and the teaching material and had been teaching Koine as a spoken, living language for quite some time in different contexts. My wife and I encouraged him to do a class for the theology students in Zurich as well, and had the chance to participate ourselves and see how this pedagogical approach might work in an academic setting. (He had already presented his method a few months earlier, and I have written about this workshop here). […]

Kommentar schreiben