This post is also available in:

Deutsch

Deutsch

Despite all the obstacles, a few women succeeded in gaining access to higher education in the last decades of the 19th century. Almost by chance, the University of Zurich played a pioneering role. In 1864, two women from the Tsarist Empire expressed their interest in studying medicine. Zurich decided pragmatically to give the applicants a chance, as no law expressly prohibited this. After 1848, liberal academics from Germany had found refuge in Switzerland. Open-mindedness prevailed, not only among foreign professors. Of the first thirty female medical students, seven graduated from Friedrich Horner (1831-1886) of Zurich, Professor of Ophthalmology.

The historian Verena E. Müller on Anna Heer as an early medical student (in German)

Only a few Swiss women

The news that Zurich would allow women spread like wildfire in Europe and even in the United States. Other Russian women followed Nadeschda Suslova (1843-1918), and Frances Morgan (1843-1927) came from Great Britain. Nadeschda Suslova was the first to obtain a doctorate in 1867. She married the ophthalmologist Friedrich Erismann (1842-1915) and moved with him to St. Petersburg. Erismann had previously been engaged to a young woman from Aargau. The abandoned Marie Heim Vögtlin (1845-1916) decided in her lovesickness to study medicine as well. Despite considerable resistance in society and family, she succeeded in convincing her father of the project. In 1868, she and the American Susan Dimock (1847-1875) began their studies. It proved to be great luck for her Swiss successors that Marie Vögtlin married the geologist Albert Heim (1849-1937). Marie Heim-Vögtlin remained faithful to her profession until her death and enjoyed great respect in the population. As a successful doctor with her own practice – and at the same time wife and mother -, she became an important role model for future Swiss female students.

Male prejudices

There were many different reasons for putting obstacles in the way of women. Were female students not physically too weak to meet the requirements of the university? In addition, it was considered improper for women to deal with sexual organs in public. Marie Vögtlin had not yet finished her studies when, in 1872, the Munich anatomist Theodor von Bischoff published a polemic against women’s studies. He argued that the female brain weighed on average 134 grams less than the male brain and studying violated women’s natural vocation. The first female students did not only have to overcome social prejudices. Girls could not attend the Gymnasium. Their education in natural science was thus mostly lacking behind.

The patients decide

It is not by chance that the first female students applied to study medicine. A helping profession fitted into the predominant image of women. Furthermore, there were firm economic reasons for such a decision. The expensive studies were an investment that had to pay off at some point. In contrast to law or theology, neither political rights nor a church permit was required for a career in medicine. The doctor opened her practice and the patients decided whether they wanted to entrust themselves to her or not.

Anna Heer on the subject of women’s studies

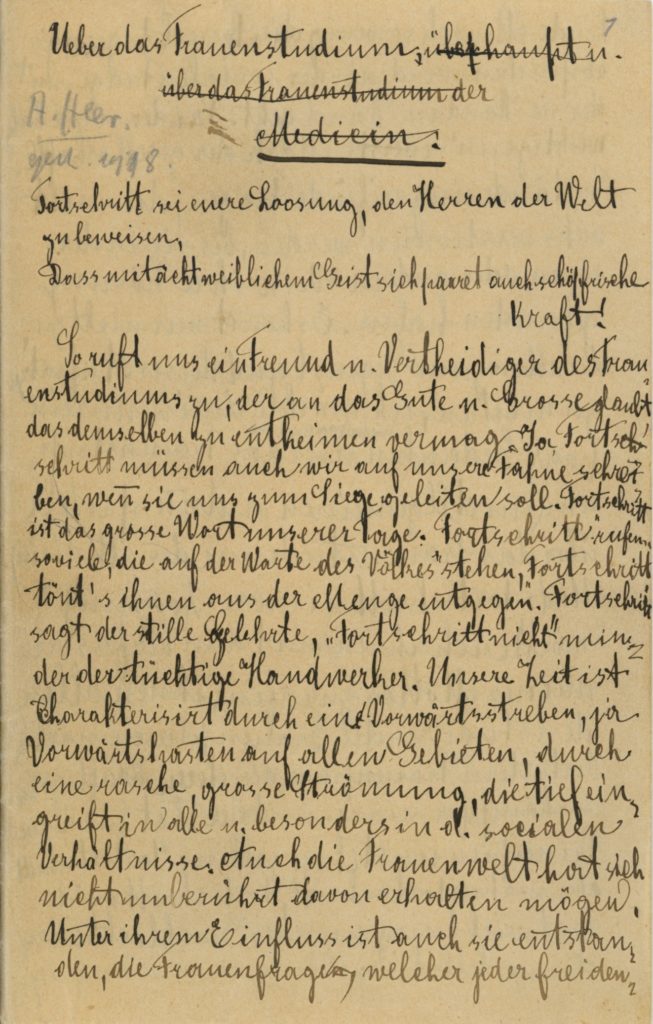

Anna Heer began her medical studies in 1883, fifteen years after Marie Heim-Vögtlin. It was already the second generation of female medical students, yet they were still fighting for recognition. The Main Library – Medicine Careum shows in its exhibition on Anna Heer a handwritten draft by her in defense of women’s studies. She emphasizes the qualification of women and the economic importance of a good education, but also hints at the difficulties a female student had to overcome. “Perhaps, with the exception of the youngest representatives, women are to be regarded as pioneers (…), who have to devote a lot of time and energy to overcome prejudices and obstacles of all kinds, and whose physical and intellectual education is often inadequate in view of their later careers.”(1)

—

Text: Verena E. Müller

1. “Ueber das Frauenstudium”, undated manuscript by Anna Heer, University of Zurich, Archive for Medical History.