This post is also available in:

Deutsch

Deutsch

In 1947, the city of Zurich honoured the dermatologist Max Tièche (1878-1938) by naming a street after him. His great achievement was the foundation of the first municipal clinic for skin and venereal diseases. Situated in the working class district Aussersihl, it treated low-income patients at affordable rates. It is less well known that Max Tièche was also a renowned expert on smallpox.

First self-experiments with smallpox

Max Tièche first conducted experiments on himself with smallpox material when he was still a young doctor. He had read about the self-experiments of the Viennese physician Clemens von Pirquet who had repeatedly inoculated himself with smallpox vaccine. After a certain time, Piquet noticed reactions of the skin, for which he invented the term “allergy”. He published his observations in 1907. At that time, Tièche had been called several times as a physician to minor smallpox epidemics. He seized the opportunity to inoculate himself not with vaccines, but with smallpox material, taken from the pustules of his patients.

Tièche carried out such experiments many hundreds of times in the following years, not only on himself, but also on his wife Sabine Tièche, who also worked as a doctor in the clinic, and on other employees. Reliably, the skin showed an allergic reaction.

Reliable test results in a few hours

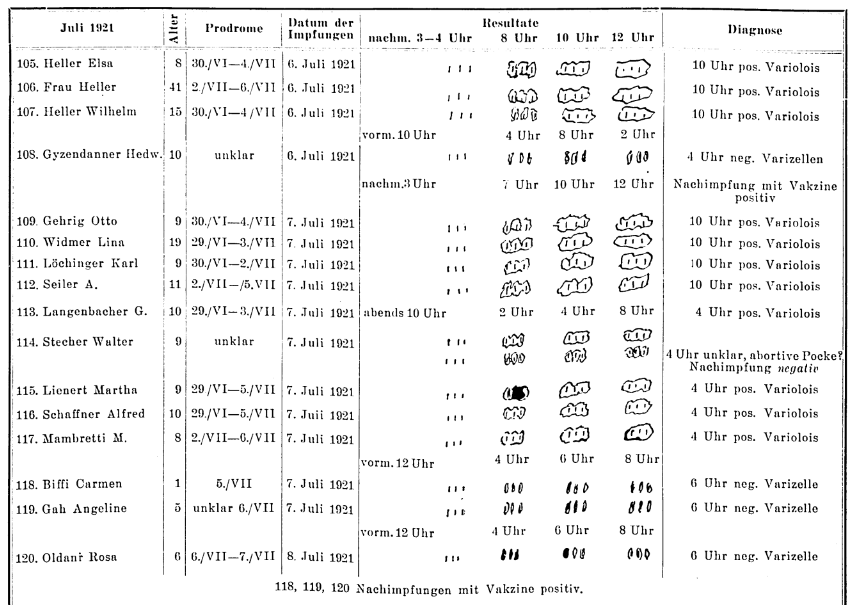

As early as 1911, Max Tièche published his new method for distinguishing smallpox from chickenpox in unclear clinical cases, but without this diagnostic method gaining acceptance. In 1921, Tièche noticed that his sensitivity had increased. He noted a skin reaction in material from a smallpox patient after only 4-5 hours, whereas it had taken over 10 hours in 1911.

Similar to the Covid-19 pandemic, the rapid and reliable diagnosis of smallpox was of great importance to detect cases as early as possible and isolate those affected. This was especially true for the last major Swiss smallpox epidemic of 1921-1925. The virus had changed its pathogenicity and was less aggressive, but was clinically hardly distinguishable from the more harmless chickenpox. Nevertheless, there was always the danger that it could become a severe disease again, as it did in other places. The possibilities for tests were limited. A standard method using animal experiments on rabbits could only be carried out in special laboratories and it took at least three days until the results were known.

It is therefore not surprising that Max Tièche became a popular medical expert in this situation. Numerous cities and regions affected by the epidemic sent him samples and sought his advice. In an obituary, the Zurich city physician Max Kruckner emphasizes Tièche’s great services during the Zurich epidemic of 1921-1923. Thanks to his rapid diagnoses, the public health officers were able to either take swift action in many individual cases or prevent unnecessary local “lockdowns” with their equally serious economic consequences at the time. It is plausible that Tièche’s diagnoses actually made an important contribution to the control of smallpox in the last Swiss epidemic.

Was Max Tièche a hero or an eccentric?

Naturally, with Max Tièche’s test method there was a risk of transmission of other diseases, especially syphilis or bacteria such as streptococci. To prevent this, the test material was either dissolved in ether, cooled or heated. Of course, a risk remained. That is probably the reason why no one could be found to follow Tièche’s example after his death.

Today, methods involving self-experimentation would not be approved by any ethics committee and certainly could not be published. Yet how did contemporaries judge this? It is striking that Tièche and his collaborators were the only ones to carry out such tests. Tièche acted as a solitary figure and there was no scientific collaboration, for example with the Clinic of Dermatology and Venereology of the University of Zurich. On the other hand, one can find numerous contemporary publications of self-experiments and experiments on staff, which were hardly discussed and certainly not made a problem.

In his admiration of Tièche’s selfless actions, the Zurich city physician Max Kruckner said: “It borders on the incomprehensible how many foreign substances Dr. Tièche absorbed into his body during the above-mentioned epidemic. Only a person who, like Dr. Tièche, is committed to the common good and who, together with his wife, his faithful co-worker and understanding helper, has always had an open eye for social welfare in general and has quietly contributed a great deal to alleviating the social misery of his charges can make such a sacrifice. “(1)

This text is based on a lecture by Dr. Michael L. Geiges, “1921 Smallpox self-inoculation as a diagnostic test: Max Tièche – Hero or Eccentric?”, History of Dermatology and Venereology Session at the 29th EADV Congress, 29th-31st October 2020.

(1) Translated from German. Original Publication: M. Kruckner. Die Bedeutung von Dr. M. Tièche für die Bekämpfung der Pockenepidemie in den Jahren 1921-1923. In: Erinnerungen an Max Tièche, 1878-1938. Zürich, 1939, S. 26.